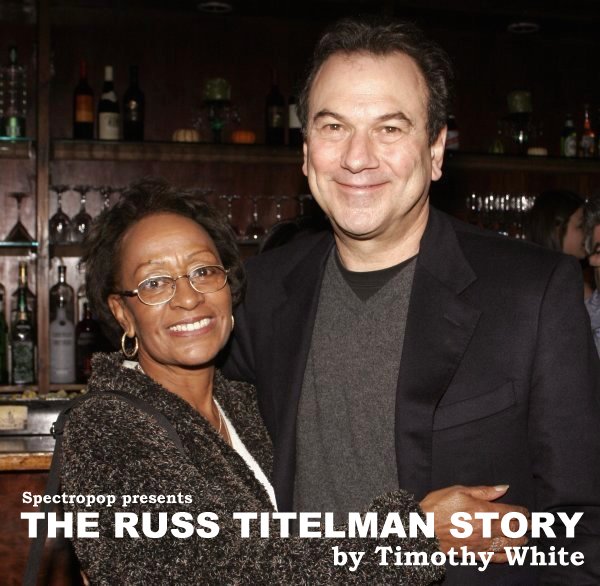

"I hadn't heard 'I Never Dreamed' in decades, and

I put it on, and while I was listening, I was thinking, 'I probably haven't

made a better record than this'." - RUSS TITELMAN, pictured

above with the Cookies' Margaret Ross, who sang lead on "I Never

Dreamed".

![]()

Lining the walls of Russ Titelman's expansive apartment on Riverside Drive in Manhattan are sepia photos of a Southern California upbringing, and of the strikingly handsome parents from Pennsylvania who gave life to him in the Promised Land. Entering the world on August 16th, 1944, the second child of clothier Herbert Titelman and the former Leonore Greenberg, Russ Titelman is a once and future boy of summer - albeit of the rock'n'roll persuasion.

Collecting early doo wop 45s like other kids collected baseball cards, enraptured by the sun-drenched Southland dream of a livelihood predicated on leisure-time pursuits, he grew up around the West Coast record industry even as that business grew up around him. The street-corner excitement of California doo wop hits and the deeply personalized industry they helped spawn in the vicinity of Fairfax High School are places in the heart to which Titelman always inevitably returns for a sense of renewal.

As a kid, music in Los Angeles was everything, exclaims the customarily coltish and enthusiastic Titelman. You'd go to Norty's record store on Fairfax Avenue, across from Canter's Deli, or you'd listen to the radio, or you'd go down to Wallichs Music City on Hollywood and Vine. And eventually you'd wind up bumping into somebody in the business because they went to these same neighborhood hot spots too.

For example, Steve Barri, who would write songs with P.F. Sloan for Jan and Dean, Barry McGuire and the Grass Roots, he worked behind the counter at Norty's! And at Wallichs Music City one day as a kid, I bumped into Kim Fowley. "Come listen to this," Fowley said, and took me into the listening booth. He had just finished producing 'Honest I Do' by the Innocents and had the acetate with him, so he played it for me! "What do you think?" he asked. What did I think? I just mumbled, "Hey, it's a hit!"

That was my teenage environment, and it was great being connected in such a casual way. The radio stations I listened to most were KFWB, KRLA, KFOX, KDAY and KGFJ with Hunter Hancock: "Running the gamut from bebop to ballad." The initial centerpiece of all this activity for me was doo wop, and it seemed that all the records I ever loved or was moved by as a teenager were things like the Moonglows' 'Sincerely' and the Flamingos' 'I'll Be Home', the latter of which got done later by Pat Boone; or 'Devil Or Angel' by the Clovers, long before it got covered by Bobby Vee. Out of the traditions of these records, and equally sophisticated ones by acts like Billy Ward and His Dominoes, came the real L.A. off-the-street-corner sounds, like ''You Cheated' by the Shields.

When you were a kid, these records spoke directly to you, about your feelings and your life. A little later, when I began writing my earliest songs like 'I Never Dreamed' or 'Please Don't Wake Me', and getting them recorded by acts like the Cookies or the Cinderellas, I knew my sensibilities had grown out of those doo wop experiences of dancing with a girl in a tight sweater, or otherwise waking up to what life was all about. I guess I wanted to help artists speak as directly to the culture as these earlier performers had spoken to me, Titelman adds with boyish intensity. And I felt that if I could do that, I'd really have accomplished something fairly worthwhile.

Thirty-five years after he strummed guitar and crooned on the Paris Sisters' 'I Love How You Love Me', Russ Titelman has written, played on or produced many of the most beloved or acclaimed records in the popular cannon. If rock'n'roll means transforming inner hungers into outreaching realities, then Russ Titelman's story is proof positive that such poignant scenarios are bona fide human possibilities.

You were a red-diaper baby, right?

Right. My parents were beyond Socialism. [Laughs] They were members of the Communist Party as far as I know. There were cell meetings at my house! I remember those cocktail parties: they were all having a good time trying to overthrow the government, I guess. I remember a guy who was being politically deported who came and stayed at our house one night; it was like the Underground Railroad.

My parents weren't in the entertainment industry. My dad's mother and father came from Russia. My grandmother on my mother's side was from Odessa; my grandfather was from Kiev; and my grandmother on my father's side, Mary Uditsk - my father's mother - was either from Latvia or Lithuania. My paternal grandfather's name was Israel Samuel Titelman. He came to America at the turn of the century and dropped an 'e' out of his name; it used to be Teitelman. So that's why everyone mispronounces it now. [Laughs]

So when they came over, they went to Pennsylvania and they started knitting mills in Altoona; they founded Puritan Sportswear. It became this very successful business. They made Ban-Lon shirts, and I remember they had Bob Cummings as the celebrity who sold the shirts. They had five sons - Frank, Dave, Mannie, Herb and Lenny - and Frank ran the company. Frank died from lung cancer in the late 1930s, and my father died from the same thing in 1956; he was a smoker. I just passed him in age.

In 1939, because of his political beliefs, my father didn't want to be

part of the company or the capitalist structure. So he met my mother when

she was 18 and he was 30, and he married her and they moved out to Los

Angeles, maybe to get away from the rest of his family. He banged around

and had a few jobs, and then when the war came he worked in the shipyards,

helping the war effort. After the war, he eventually went back to the

family company as the West Coast salesman for Puritan. One day, he had

a meeting at the May Company store on Fairfax and Wiltshire, and there

was a picket line there, so instead of going in, he got on the picket

line! Somebody from the store saw him and called Frank in New York and

said, "Your crazy brother is on the picket line, get him off or we're

not gonna buy any more of your stuff!" Years later, Frank's son Dick,

who was certainly not left-wing, said to me, "Your dad was a good

guy. He was a man of principal."

How did music and the record business come into your household?

That's an intricate story. My parents were into music. My mother told me that when they first moved to Los Angeles, the used to go to this bowling alley, next to Wallichs Music City on Vine Street and listen to the Nat Cole Trio. At home, they had Nat Cole records, Louis Armstrong records, Leadbelly, the Almanac Singers, the Weavers - and the Red Army Chorus on some 78s, naturally. [Laughs] And my father's favorite classical piece was Beethoven's 5th Piano Concerto played by Artur Rubenstein; he listened to that all the time. And when I went to Westland School on La Cienega for kindergarten, Carol "Cookie" Cole, one of Nat's daughters was in my class.

Later, when I was at John Burroughs Junior High School, my sister Susan, who's two and a half years older, was going to Fairfax High School, the "rock'n'roll high school", attended by Mo Ostin, Lou Adler, Phil Spector, Herb Alpert and Steve Barri. Susan's best friend was Phil's girlfriend, Donna Kass, and Susan was dating Marshall Leib, who was a member of Phil's group, the Teddy Bears.

At the time, Phil was studying to be a court reporter at Los Angeles City College, but he was a great jazz guitar player and was taught by Burdell Mathis, the same guitar teacher Phil recommended I take lessons from, which I did. Burdell's place was across the street from Wallichs, the store owned by Glen Wallichs, who helped start Capitol Records. Burdell taught me for about a year, and I played on a Gibson L12.

Anyhow, I was in the second grade [sic] when I'd come home from junior high each day and the Teddy Bears would be rehearsing in my living room. Meanwhile, I used to go to the Rexall drug store on La Cienega and Beverly with my friend Bobby McKay, and we used to steal 45 records like 'Whispering Bells' by the Del-Vikings and stuff them in our pants. We got caught, and my mother came and picked us up; my father had just died a year and a half before and my mother was very worried about me. My punishment was to be sent to Calamigos Ranch, a nice camp in Malibu, in the summer of '58. Such a punishment!

While I was at camp, Phil and the Teddy Bears went into Gold Star Studios

and cut this song they been rehearsing in my living room, 'To Know Him

Is To Love Him'. During one of their visits to my camp, my mother and

my sister brought this record and played it on this ratty little portable

record player there. I just thought, "Wow, what a thing!" It

got released, went to No. 1, and I saw Phil on American Bandstand. After

that, I idolised him and just wanted to be around Phil all the time. He

went on to make more Teddy Bears records and an album for Imperial, and

he used to come over to our house with the mastertapes, asking me, "What

do you think of the drum sound?" So that's how I got interested in

music and the record business.

How did you start your own recording career?

Well, at one point I didn't see Phil for a while, and then I was coming home from school one day and he drove by in this cool Corvette. I waved, and he gave me a ride home, and he had this instrumental record that sounded like Johnny and the Hurricanes that he did under the name Phil Harvey - his real name is Harvey Phillip Spector - and the record was called 'Bumbershoot'. He invited me to go to a hop at the Rainbow Roller Rink in the San Fernando Valley, where he and his little band were performing the song. DJ B. Mitchell Reed was the host, and Edd "Kookie" Byrnes was there miming 'Kookie, Kookie (Lend Me Your Comb)'. Phil got into a fight with Reed, because they weren't gonna pay Phil, and that seemed dangerous, because this wasn't our neighborhood; it was a more Latin neighborhood, and we were outsiders.

So afterwards we continued to hang around together, and the day my sister

graduated from high school, Phil asked me to sing falsetto on a demo on

a studio session at Gold star. Phil thought my voice was OK, and so when

he started working with the Paris Sisters, I sang backup and played guitar

- a Gibson ES335, I think - on this 1961 song of Phil's they did, 'Be

My Boy', which was a decent hit. Next, Phil went to New York and picked

up a couple of songs from Don Kirshner at Screen Gems/Columbia Music,

Barry Mann and Larry Kolber's 'I Love How You Love Me' and 'He Knows I

Love Him Too Much', a Carole King and Gerry Goffin song. We went in the

studio and made a Paris Sisters album, and so I played and sang on all

those Paris Sisters songs.

How did you become part of the Spectors Three vocal trio?

Well, the Paris Sisters were recording for Gregmark Records, and at the same time Phil was working with Lester Sill and Lee Hazlewood, who also had Trey Records. Phil wrote these other songs, 'I Really Do' and ''I Know Why', and Phil and I sang them with Phil's girlfriend, Rickie Page, for Trey as the Spectors Three.

But Phil didn't want to appear in the promo pictures or at the personal appearances and he didn't want Rickie to appear either, so he said, "Who can we get who's good looking?" I said, "I've got this beautiful girlfriend, Annette Merar." So we got Annette and my friend Warren Entner, who later was in the Grass Roots and much later became the manager of Quiet Riot and Faith No More, and we were in the photographs for the Spectors Three. We also appeared on the Wink Martindale Show with Sam Cooke, Jewel Akens and others, and we mimed the record. And Phil later wound up marrying Annette.

Then Phil went to New York for a long while, and I started hanging around

with Ed Cobb, who was the bass singer in the Four Preps. By then I was

taking guitar lessons from Ray Pohlman, the famous session guitarist for

Phil and so many others, who lived with his wife Barbara in Beachwood

Canyon, and he brought me to play on a bunch of Ketty Lester records like

'Once Upon A Time'. And he and Ed and I cut an instrumental version of

'High Noon', which I'm not sure got released. By then, it was 1962 and

I'd graduated high school and went to Los Angeles City College.

What was your major in college?

Actually, I took theater arts, with a mind to become an actor. Paul Winfield was there at the time, and when I saw him do a scene from The Emperor Jones, I thought, "If I live to be 150, I'll never be able to get to that level." So I made a choice to quit acting and pursue a music career.

As this was going on, I was writing songs as well, and I had a high school friend named Barry Froner, and his dad gave me a thousand bucks to record my songs at Gold Star. I found a couple of girls to sing, went into Gold Star with engineer Larry Levine, and Gene Page, who I'd met, put a little arrangement together with chord sheets. Gene's brother Billy, who later wrote 'The In Crowd', went into the studio with other musicians and me on acoustic guitar.

We demoed 'Just A Little Touch Of Your Love' and some other songs, which I took to Lester Sill in his office on Sunset Boulevard, who I knew from Spector. Lester took the songs upstairs to Screen Gems/Columbia. Donny Kirshner loved 'Just A Little Touch Of Your Love', and I got signed to Screen Gems. The song got released eventually on the Guyden label by this singer with a smoky voice, whose name was Saundra Franklin, but there was a tonal error on the master and it didn't sound right. It crushed me, since it was my first record, but, hey, now I was writing for the same company where Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, Goffin and King, Neil Sedaka and Howard Greenfield and my other idols were!

I met Barry Mann in the summer of 1963 and he said, "I loved your song, come to New York and we'll write together." So I did, and I stayed at the Hotel Earl. So Cynthia and I wrote these two songs together, which Barry and I co-produced, 'Baby, Baby (I Still Love You)' and 'Please Don't Wake Me', which were done by the Cinderellas for Dimension Records.

Going to work at the Screen Gems office every day in the Columbia Building

on 711 Fifth Avenue, I got to know Carole King and Gerry Goffin, and I

did some work with Gerry, including 'I Never Dreamed' for the Cookies

and a song called 'What Am I Gonna Do With You', that was recorded by

Lesley Gore, and the Chiffons and Skeeter Davis did a version too. I also

wrote 'Yes I Will' with Gerry, and Carole fixed a few notes on it and

made it what it was: a Top 5 record in England in 1965 by the Hollies,

and then the Monkees recorded it as 'I'll Be True To You' on their first

album.

|

|

|

|

[Click to enlarge] | ||

During this period, you also wrote songs with Brian Wilson, didn't you?

Yes, we co-wrote 'Sheri, She Needs Me' and 'Guess I'm Dumb'. The second one was recorded by Glen Campbell; a Japanese woman just recorded it, and it was on a Japanese album that sold about 700,000 copies. Can you imagine?!

Anyhow, meeting Brian was part of being at Screen Gems, because Brian used to visit Lou Adler all the time in the L.A. office. I'd be around, too, and so I saw Brian a lot. I also used to go over to Brian's office, a big office in a bank building on the southeast corner of Sunset and Vine where he'd go to write songs. I'd also go over to Brian's Hollywood apartment, which was spartan to say the least, but he had a piano in there. He loved Jonathan Winters and he used to sit around and recite all the Winters bits and laugh his head off; he could do a real good imitation of Maudie Fricker. It was fun. 'Sheri, She Needs Me' was written on the piano at the house of his girlfriend, who became his wife, Marilyn. And 'Guess I'm Dumb' was written at Marilyn's and at his apartment.

One day when I visited Brian at the office, he was writing 'Fun, Fun,

Fun', but the lyric he had at the time was 'Run, Run, Run'. He had a whole

other lyric to it, and it was a good song that way, too! He was like a

kid, going around barefoot in a T-shirt and jeans. I was never a fan of

his early surfing records, but when he started idolizing Phil Spector

and it was orchestral surf music, then I got interested in it.

I loved the spontaneity of what was coming out of his head. Later, I thought

'Pet Sounds' was way ahead of anything of Phil's. As great as Phil was,

his orchestrations were all the same kind of thing. But Brian's didn't

have a formula!

So how did you find your way into the house band of the Shindig! TV show?

After spending nine months in New York, writing each day in a bunch of cubicles with pianos in an office that was run by Charlie Koppelman and Don Rubin, I hadn't had a lot of really big successes. I was living out in East Orange, New Jersey, sharing an apartment with Ethel "Earl-Jean" McCrea, the lead singer of the Cookies, and her sister Darlene, who was one of the Raeletts for a while, who I was dating. I also wrote a song for Darlene McCrea called 'My Heart's Not In It', but it never did anything.

Then I got a phone call from Ray Pohlman, and he said, "Come home. We're doing television, and you'll play guitar!" So I went home in October or November of '64, and it turned out to be Shindig! I was in the Shindig! band; the Shindogs, incidentally, was a separate group on the show. The Shindig! band was Richie Frost on drums, who played on all the Ricky Nelson records; Larry Knechtel played bass; Leon Russell played piano; Julius Wechter from the Baja Marimba Band was the percussionist; Jerry Cole was the lead guitar player; I played rhythm. There was a horn section, too. Then things changed, with James Burton and Billy Preston in the band for a while; Paul Humphries, too.

We backed up people either by taping the tracks beforehand or by doing it live. We backed Jerry Lee Lewis live on 'Whole Lot Of Shakin' Goin' On', and he was great. During that time, I also played on some Phil Ochs sessions, some Righteous Brothers sessions like 'Hung On You', and I conducted the choir for some of the overdubs on 'Just Once In My Life'.

Plus, I went to a few Beach Boys sessions with Brian, and he asked me to take a screwdriver and bang on a mike boom during 'She Knows Me Too Well'. That "tink-tink" you hear during the song, which sounds like a triangle, is me on screwdriver and mike boom. [Laughs]

Meanwhile, I became friendly with Jack Nitzsche, who was producing movie soundtracks, and I played on the score for the horror film Village Of The Giants. Jack and I used to go over to Metric Music, too, to see Lenny Waronker, who was a publisher, and we'd ask what the latest thing was. Lenny would say, "Listen to this!" and that's how we heard Jackie DeShannon's 'What The World Needs Now Is Love' before it came out.

Then I left L.A. after about nine months and traveled around Europe in 1966. Nitzsche came over to England and said, "You have to come see this group," who were playing in this little room, and it was the Troggs, who had just made their demo of 'Wild Thing' and 'With A Girl Like You'. They got signed over here to Atco.

I came back to L.A. around Christmas '67 and did a lot of sessions with

Nitzsche. I played 12-string on the Buffalo Springfield's 'Expecting To

Fly', which was a Nitzsche arrangement. Later, I played on Jack's soundtrack

to the film Candy, which was rejected. Otherwise, like a lot of other

people back then, I just hung out and smoked pot and listened to Beatles

records. [Laughs]

|

|

Above top: with Charlie Greene (left) and Jack

Nitzsche (right), Copenhagen, 1966. |

In 1969, you found yourself playing guitar on 'Memo From Turner', for Jack Nitzsche's soundtrack to the Mick Jagger film, Performance.

Actually, the core of the studio band on that record was Randy Newman, Ry Cooder and myself, and it was recorded in Los Angeles at Western Studios. But Jagger wasn't there during our sessions. The band Traffic had done a recording of 'Memo From Turner', but Jagger and Nitzsche didn't like it. So we replaced their track, playing along to Jagger's existing vocal and a click track. I played the Keith Richards-sounding "jing-a-jing" on rhythm guitar, and Ry Cooder did the slide guitar parts.

And then Jack and I wrote 'Gone Dead Train', and Randy Newman sang it,

and we cut it live. They needed a song for the credits and Jack said he

wanted to lyrically use all this voodoo and blues terminology for this

story of this faded rock star, a burnt-out character who can't get it

up anymore. I saw the track part as Chuck Berry-like in feel but more

raucous.

The Performance soundtrack marked your first recording for Warner Brothers Records, but what were the exact circumstances that led directly to your 25-year association with the label?

Well, in the early '60s I used to go over to Reprise Records on Melrose and hang out with Steve Venet, who was the head of A&R there; Steve was the brother of Nick, who produced the Lettermen for Capitol. Anyhow, this was before Reprise, Sinatra's label, was sold to Warners, and I used to see Mo Ostin there. Everything was completely informal then.

But, really, I was getting to know Lowell George at the time of Performance in 1969 that sorta led to Warner Brothers as a full-time thing. See, Lowell George, who worked uncredited on the Performance soundtrack, was a big fan of Ravi Shankar. Shankar had opened a school, the Kinara School of Music, and I met Lowell there because I was studying sitar there for a year. Although I couldn't play sitar that well, Lowell could. Incidentally, George Harrison, who I would later produce, also came by and we were introduced. So Lowell and I got close and drove around all the time in this Morgan car he had, taking LSD and mescaline. Lowell was amazingly talented. He was a flute player in high school, and he knew how to play Japanese shakuhachi flute; anything he picked up he could figure out, and he of course was a truly great guitar player.

As we were studying sitar, Nitzsche was doing this Performance movie score with all sorts of different instrumentation, and I said, "Look, we'll have tamboura and veena," which I borrowed from the school. I played veena on one song, Buffy Sainte-Marie played these mouth-bow solos, and Lowell and all of us did this crazy stuff on the tracks. Jack also was smart enough to get Ry Cooder to come and play all this slide guitar. My sister Susan and Ry had met by then, but they weren't married yet. Four years on, I would co-produce Ry's 'Paradise And Lunch' album and co-write 'Tattler' with him, so Performance was the beginning of a lot of associations.

Meanwhile, Lowell was simultaneously playing with the Mothers Of Invention, and he was rehearsing his own band, Little Feat, and Lowell was going to sign with Lizard Records. But Lenny Waronker had gone over to Warner Brothers by then, so I said to Lowell, "Don't sign a deal with Lizard until we go over to Warners and see Lenny!" I called Lenny and said, "There's something you should hear!" Lowell and Billy Payne and I went to see Lenny in his office, where Lowell played guitar and Billy played piano and they sang 'Willing', 'Truck Stop Girl' and 'Brides Of Jesus'. Lenny said, "This is great! Go talk to Mo! Go make a record!" It was that simple. I produced the first 'Little Feat' album, and some of it was the demos we'd made, like 'Truck Stop Girl' and 'I've Been The One'. So that was when I first started working for Warner Brothers as a producer, which was in 1970; but I wasn't hired until July 1971, because I was like a hippie and I didn't want a full-time job.

The next thing I did after Little Feat was the 'Randy Newman/Live' album.

I'd first met Randy at Metric Music, but we'd come to know each other

well because of Performance. But I think I owe my job and my co-production

partnership with Lenny to the USC football team. See, Randy was performing

at the Bitter End in New York for three weekend nights; we recorded him

from a mobile truck outside, and it was snowing and freezing cold. In

the cab on the way down to the first night's taping, Lenny Waronker had

said, "Why don't you sit in the truck with me and we'll be co-producers?"

I said, "OK!" So we both sit in the truck that night, and then

Lenny suddenly says, "I have to go back home, but you stay here in

the truck: it'll be OK." I said, "Huh? What do you mean? What

is it?!" He said, "It's the USC football game." Lenny was

a USC alumnus and felt he had to go back to L.A. to see this football

game, so I stayed in the truck and finished the taping. I mixed 'Randy

Newman/Live' at Western Studios, chose the best performances, put it together.

And it was a really nice record. On live records, you always get this

extra passion that's not possible any other way. I mean, see 'Unplugged'

by Eric Clapton. So then Randy and Lenny and I started working on Randy's

'Sail Away'.

Looking back, what were the high points of producing Randy Newman with Lenny Waronker, since, besides 'Live' and 'Sail Away', you also worked on Randy's 'Good Old Boys', 'Little Criminals', 'Born Again' and 'Trouble In Paradise' albums?

[Smiles] The high points, in a way, were getting the phone calls before we'd record, with Randy saying, "Come over to the house, I gotta play you something," and having it be 'God's Song' or 'Sail Away' or 'Marie'. I cried when Randy played 'Marie' in his little workroom in his house in Pacific Palisades. When Randy wrote 'Marie', he was working on a project that was gonna be called 'Johnny Cutler's Birthday', about this Southern guy, a roller in a steel mill; this Southern opus. That record became 'Good Old Boys'. 'Marie' is beautiful. Randy wrote it about a girl named Marie he was once madly in love with; it's like a Stephen Foster song. And the other song that really kills me that he wrote, it's so deeply emotional, and Linda Ronstadt recorded it, is 'Texas Girl At The Funeral Of Her Father', which was on 'Little Criminals'. Randy is so funny, and so smart, and the songs were so brilliant. All I can remember is that we used to laugh all the time. It was fun making those records, laughing nonstop about his sick point of view.

|

You've worked with some of the great singer-songwriters in rock'n'roll history, including James Taylor for his 1975 'Gorilla' and 1976 'In The Pocket' records; Rickie Lee Jones on her 1979 debut album, her 1981 'Pirates' and 1995's 'Naked Songs'; and George Harrison on his self-titled 1979 album. How would you compare and contrast these artists?

Rickie Lee is such an unusual figure, because she was literally very streetwise from being a bohemian of sorts and even a runaway at one point in her youth. She literally dropped to earth as a natural songwriter whose work was excellent from the very start. But what Lenny Waronker and I found fascinating was that she had never been in a studio before. She grasped the art of doing vocal composites and other techniques very quickly, learning to play the studio as if it were an instrument. Personally, she was very fragile on her first record, at once very powerful and terribly vulnerable, because her difficult personal and family background made it hard for her to trust in the way you must in the studio. We could tell from the humor and colorful characters in her songs that she'd led an unusual existence before we signed her, but, in fact, as Lenny later remarked, we actually had no idea how intense the hardship had been in her past until we read the Rolling Stone cover story that you yourself wrote about her in 1979. The story was very eye-opening for a lot of us at Warners. More than once, Lenny and I said to each other, "Boy, that piece really explains a lot," because Rickie Lee could only open up just so much in the studio, and in that interview she trusted on an even deeper level. By the time of Rickie Lee's 'Pirates' album, you can hear that she'd learned to trust, especially in the gripping vocals on 'Pirates (So Long Lonely Avenue)' and 'We Belong Together'. We got in the habit of waiting for her magic performances, and they'd always occur.

James was such a pleasure to work with because he was so intelligent and had such a broad knowledge of the blues, country and western and American music of all sorts, whether it was Aaron Copland, Hoagy Carmichael, Jerome Kern or George Gershwin. His songs had great humor and an edge of the sardonic, but also compassion and sweetness. I love James' harmonic sense and the emotions he inspires in his listeners with what he writes. 'Shower The People', 'Sarah Marie', 'Lighthouse' - those songs stunned me and choked me up. But the most powerful song was 'Junkie's Lament'. That was recorded at a tough time in James' life, which he has long since grown past, but the fact that he could open his soul and confess that stuff was chilling yet admirable.

With George Harrison, there was a certain awe I had to get past, but

I came to understand the specialness of what he brought to the Beatles

and to popular music in his solo work. George's guitar style and sounds

are incredibly unique, but it's important to realize that George was not

that much of a jamming soloist, as Eric Clapton was and is. So all George's

unforgettable Beatles solos were very deliberately thought out. He was

a craftsman of the highest order and he remains that kind of player in

his solo music. The fluid approach he got from India was in songs on 'George

Harrison', like 'Dark Sweet Lady', 'Love Comes To Everyone' and 'Blow

Away', which is a phenomenal pop single. A lot of people don't realize

that 'Blow Away' used the rebuilding of Friar Park, the broken-down nunnery

that he restored as his family home, as a metaphor for how he had to rebuild

his life after the Beatles broke up and his marriage to Patti Boyd ended.

The song has a brilliant lyric and musical structure. George also brought

both a very confident spiritual dimension and a knowledge of world music

to pop music that it had never had previously. Things like that take guts

and an inner will.

Let's touch on other peaks of your long career. In 1973-74, you did the first two albums with Graham Central Station, the self-titled debut with the hit 'Can You Handle It?' and the ''Release Yourself' record. Larry Graham was an amazingly influential pioneer of the deep funk sound.

[Nodding] Larry was the bass player with Sly & the Family Stone. He had a falling out with Sly and put that band together, and he had been writing all along. Mo Ostin sent me up to San Francisco with Don Schmitzerle, and we flipped out when we heard Larry's demos. I was fortunate to be co-producer with Larry on that record, because Larry invented modern R&B bass. There's a song on that record called 'Hair' that sounds like three guys are paying bass. I talked to Marcus Miller about it much later, and he said he had a vinyl copy of the 'Graham Central Station' album and he'd slow it down to 16rpms so he could learn Larry's part on that song!

Tell me about working with Chaka Khan in 1983.

That came about from Bob Krasnow, who was working for Warner Brothers at the time, and he heard an album I made in 1982 with Bill La Bounty, a very good songwriter and singer who lives in Nashville now. He was putting together this swansong for Rufus and Chaka Khan, their last record together, and it was gonna be this 'Live/Stompin' At The Savoy' project with live performances and some studio cuts. So Bob heard that La Bounty record and said, "You're the guy to do this." I'm glad he had faith in me. We went to New York and recorded a bunch of these shows at the Savoy, and also got an opportunity to go in the studio with her. It was one of the most amazing experiences of my life; I was just thankful to be there; it sent chills down my back. She was one of the most natural geniuses I met, and I don't use that term loosely. The crowning glory of our relationship was when she did 'Ain't Nobody' for the studio part of the record. And my mouth dropped open when she sang it. That track was very sparse, and the main focus was her vocal. David "Hawk" Wolinsky wrote and arranged that song. It was a truly passionate record.

A year later, I worked with her and Arif Mardin on the 'I Feel For You'

album, which was a crowning achievement of the Mardin/Khan partnership.

And Arif was kind enough to hire me to produce 'Eye To Eye', a Michael

and Danny Sembello song, on which her harmonies and the meaning she brought

to the lyrics were just incredible. Then I did 'Tight Fit' with her on

the 'Destiny' record. Two years later, in 1988, we did the 'C.K.' record,

whose highlights were 'End Of A Love Affair', which George Benson played

on, and the Billie Holiday classic 'I'll Be Around', which Dave Grusin

arranged, as he did the former track. Prince sent us two tracks, with

Miles Davis playing and talking on one, 'Sticky Wicked'. It was his vocal

debut, and on the track Chaka suddenly said, "Say 'sticky wicked'."

Miles growled, "You want me to say 'sticky wicked'?!" It was

pretty funny, and we kept it. Chaka always has her signature licks that

no one else can do, but she also has these absolutely breathtaking surprises

all the time. So the job of the producer is to make her feel comfortable

enough to surprise herself and you too.

'Hearts And Bones', which you co-produced in 1983, may be Paul Simon's most underrated album.

I met Paul after hearing the soundtrack to his movie One-Trick Pony, and I became friendly with him. Over the course of the time we spent together, he just pulled me into his next project, which turned out to be 'Hearts And Bones'. Lenny and I were working together with Paul on 'The Late Great Johnny Ace', 'Song About The Moon' and 'Allergies' and other early songs for the record when Lenny became president of Warner Brothers, so Paul, Roy Halee and I finished the record. Paul came in with the basic songs, just his guitar and voice, and we'd go from there. Paul is so thoughtful about his process, very careful, but very open to the unexpected. That record came at a time in his life that was very emotional. In some respects, the album is the story about the breakup of his marriage to Carrie Fisher and where he was at that time. Much of it, like the beautiful 'Train In the Distance', is about expectation and loss. Actually, a lot of his songs are about attaining something, or walking away from it, or personal longing. The singer Johnny Ace was not really a doo wop artist, but he was from that general era, and the song ''The Late Great Johnny Ace' evokes the feeling in a way of what those doo wop records were about. Sonically, it's about a time gone by. And the track 'Rene And Georgette Magritte With Their Dog After The War' is Paul's homage to those doo wop groups, and to juxtapose them with Magritte is this brilliant leap. In the song, they undress, open their bedroom drawers looking for these hidden things, and within the drawers is the music of these doo wop groups, the Penguins, the Moonglows. This "deep forbidden music".

You've worked with a lot of jazz and R&B artists, like George Benson, David Sanborn, Patti Austin, Womack & Womack.

[Nodding] And also Jocelyn Brown, a great singer who lives in England. I did her 'True Love' single in 1986, but she also sang backup on Steve Winwood's 'Back In The High Life' album, on 'Split Decision'. They were all very different experiences, but I love the R&B talent all these people have in their own way. For instance, Dave Sanborn does things with a sax that nobody's ever attempted, groundbreaking ways of pushing the sound of the instrument.

Cecil and Linda Womack do a style of music, a country soul that's a direct link to the gospel of the Soul Stirrers or James Cleveland. Whether on their 'Transformation To The House Of Zekariyas' album I did with them in 1983, or with a song like 'New Day', which is like an even more directly spiritual, more direct version of Sam Cooke's 'A Change Is Gonna Come', their stuff has the quality of a plaint. And then there's the song Womack & Womack wrote, called 'Lead Me On', that Eric Clapton sings on 'Journeyman'. If you listen to that song, it's a romantic storyline where the man says to the woman, "Tell me anything you think I wanna hear just to keep me standing here," and it's like a complex play, with hope and deception interwoven.

As writers, Cecil and Linda Womack get a groove and then go with it, letting it take them where they feel they should go. George Benson has a similar instinct. I'm not a big jazz person, and George's '20/20' was a more R&B-like record. I have a few favorite things on that record, one of which is 'I Just Want To Hang Around You'. I made Michael Sembello give me that song for George; I think maybe he promised it to somebody else. I also loved the Frank Foster/Ralph Burns arrangement of 'Beyond The Sea', and the Womack & Womack song 'New Day'.

Patti Austin came in one day to sing the harmony part on the title song

'20/20' and, bang, hit it in one take. She's really underappreciated,

even though she's done those exquisite hit duets with James Ingram for

Quincy Jones, 'Baby, Come To Me' and 'How Do You Keep The Music Playing'.

I was also happy with the title track we did for Patti's 'Getting Away

With Murder' single. She's always amazing with other people and makes

it look easy, just like she did with George Benson.

'20/20' is probably Benson's best album as a vocalist.

George worked hard on it. I remember when I got done with '20/20', I played it for Lenny Waronker, and he said, "This is so perfect. It's exactly what George should be doing, this Sam Cooke kind of stuff." My only regret is that I didn't get George to play more guitar. To me, George Benson and Eric Clapton are the two greatest living guitarists.

Steve Winwood's Grammy-winning 'Back In The High Life' of 1980 is his finest solo record in every vocal and musical sense. It's his most eclectic, arrangements-wise, features him on lead guitar as well as keyboards, and it has the most intriguing cast of support people, like James Taylor singing backup on the title track.

The song 'Back In The High Life' originally had an island-like feeling to it, very up and Caribbean in feeling. I brought Jimmy Bralower in for some drum programming, and when he and Steve got together they slowed it down. It just made me think of James Taylor, since it was not unlike one of his songs.

I'd met Steve when I produced George's 'George Harrison' record in 1979. We called him, and he drove down with his Prophet synthesizer and harmonium and started playing away with that trademark Winwood saxophone synth on 'Love Comes To Everyone' and the string-like stuff on the hit 'Blow Away'. We had a real good time, and then a few years later I was working with Christine McVie, and she loved Steve and wanted to work with him, so he came in again, and they wrote a nice song together, 'Ask Anybody'. Afterwards, when Steve decided he wanted to get an outside producer for his solo recording, that was probably one of the basic factors for wanting to work with me.

'Back In The High Life' was an eight-month project, with most things

written except for 'Split Decision', which he did later with Joe Walsh.

Steve's lead guitar on the record was tremendous on things like 'Take

It As It Comes, and his rhythm playing on 'My Love Is Leaving' is so muted

and poetic. Overall, some of the recording was planned, but a lot just

happened as we went along. For Steve, he'd made great records on his own,

but he really wanted to stretch out as a singer, a writer, a player. I

was fortunate to be there at the time, and I feel that basically I was

a casting director in a lot of ways. In the end, I feel if a guy's a great

producer, you don't know he's there. There's a style in production where

the artist is inconsequential, the auteur style. But then there's the

style where the job is to sublimate the producer's presence. You always

get your stuff in there anyway, but the emphasis should always go back

to what the artist wants, needs, requires. Find it fast for the artist

and put it at his service so things can keep going.

|

|

From 1989 to 1994, encompassing Eric Clapton's 'Journeyman', '24 Nights', 'Rush' soundtrack, 'Unplugged' and 'From The Cradle', you helped him produce the finest sequence of work in his entire career. He was so mature in his art and so healthy he even quit smoking. It must have been remarkable to see someone so established reach such a transcendent new stage. This work will always be considered the commercial and artistic golden age of Eric Clapton. How does it feel to have shared so much with an artist who's so important?

It's a great honor. I think for a long time I was someone he could count on for support and to bounce stuff off of. We had a very good and open working relationship. 'Journeyman' was a deep collaborative effort because I listened to everything he'd done in the past and I wanted him to go further. I'd known Eric since he played on 'Love Comes To Everyone' from the 'George Harrison' album. But I don't think I was ever more nervous going into a session, and I had no idea what he was gonna be like.

But he had a great band, with bassist Nathan East and drummer Steve Ferrone and all his buddies. But he had never worked with pianist Richard Tee, who we brought in, or Womack & Womack. And then George Harrison wanted to participate, and he'd written five songs for Eric, and he and Eric came over my house in Connecticut and went over them. We chose 'Run So Far' for 'Journeyman', a very plaintive, sad song. And then Eric put George's 'My Kind Of Woman' on the 'Romanian Angel' charity record. It was just so cool. And throughout, Eric played his ass off on guitar.

Now, the arrangements on '24 Nights', like the give-an-take with singer Katie Kissoon, those were Eric's arrangements. The challenge on that project was to capture all the diversity of his live shows at that point in his life, whether it was electric blues with Buddy Guy and Robert Cray and his other friends, his full band sound, or his hits.

The 'Unplugged' record was actually the record we almost made instead

of 'Journeyman', because we threw around the idea of a serious blues record.

And by the way, the Grammy-winning version of 'Tears In Heaven' is not

the version on 'Unplugged'; it's the studio version from the 'Rush' soundtrack

- which was a great experience too, because it harkened back to the days

of making records quickly. We had to make 'Rush' in a few days, so I ran

around and even brought in a Celtic harp player I knew from high school,

Gayle Levant, who I hadn't seen since I used her on 'Mexico' on James

Taylor's 'Gorilla' record.

|

All the relationships from your youth still endure, including the ties with Brian Wilson that led to your co-producing his solo record over two decades later.

It's wild, isn't it? Just listen to Gayle's ethereal harp on 'Tears In Heaven'. It really helps make that record what it is. [Somber] But it was very difficult for Eric to record the vocal on that song, since it concerned the loss of his son. It was hard for all of us when it came to that moment. 'Tears In Heaven' hit people so deeply, and he became such a focal point with his suffering, but I also think it opened the way for Eric to do 'Unplugged' and 'From The Cradle', because the public became interested in him as a man as well as an artist.

And I want to say something here. The effect Eric had on me was a mighty

thing. Just being around him personally, I stopped drinking while I was

working with him. I was going through a tremendous emotional thing at

the time myself. My marriage broke up a year or so after ''Journeyman',

and while my ex-wife and I are still as close as we could hope to be,

being around someone with as much samurai/ascetic spirit as Eric taught

me a great deal. Eric spent a lot of time alone with that guitar when

he was a kid. That's why he's so great. But it's also a quality of artistry

that comes out of self-examination. All of the study, pain and loneliness

he went through as a young man strengthened him. I found it easier to

look at alcohol intake or my own pain from being around someone like him.

We still talk from time to time, and I remember that when we finished

'From The Cradle', I went down to Antigua to play him the final sequence

of the tracks. That got done in short order, and then we spent a whole

day just talking about life, emotional stuff and relationships. It helped

me through a hellish time.

Is there anyone else in your career who's had as profound effect as Clapton?

Yes. I would also have to say that Lenny Waronker has. Lenny was always like a big brother to me, a constant source of support, making me feel that, no matter what I did, he would believe in me. Because of the tone Mo Ostin and Lenny Waronker set at Warner Brothers, you were free to try all sorts of unusual things, but most of all you were allowed to fail and not be penalized for that, because Mo and Lenny understood that failure brought growth just as much as success does; maybe more.

Working with Lenny, I was always thrilled with the great gift of musical

imagination that he has. He may have gotten some of that from his father,

who was first violinist and concert master for the 20th Century Fox orchestra

under Randy Newman's uncle, Alfred Newman. Lenny always had very cinematic

concepts of how rough tracks could be worked on. During the making of

James Taylor's 'Gorilla' album, I recall Lenny coming up with these different

ideas as we drove home from hearing James' demos for the record. Interestingly

enough, the next day he presented them to James as things he might want

to explore, rather than as full-blown suggestions he had to follow, thus

allowing the artist the creative room he needed. That showed Lenny's typical

knack for tact and sensitivity.

It's not often in life that adults get a chance to share ideas and offer aid and comfort to each other with such meaningful, public end results. Do you think all these things would have happened if you hadn't gone to Fairfax High?

No. [Smiles] I think if I hadn't been there, and my sister hadn't been the girlfriend of Marshall Leib, I might be in Ban-Lon shirts and working in the Puritan warehouse, filling orders. I suspect folks like the music teacher at Fairfax High - Homer Hummel - had some influence on me, since he was my instructor for school choir practice. However, having actually worked in one of those sportswear warehouses when I was 15, I suspect that that experience, more than anything else, may have been the incentive to get into music!

(This article originally appeared as Please Don't Wake Me: Producer Russ Titelman Recalls 35 Years In The Service Of A California Dream in Billboard, June 22 1996. Republished with permission of the author.)

PRESENTED BY THE SPECTROPOP TEAM