|

Such high praise comes from music industry veteran Tom Kennedy,

head of promotions at Jamie Records during the Kit Kats' legendary

run there. Kennedy's memories of the band are not unique;

he eloquently summarized the feelings of many of the Kit Kats'

fans and associates. But these sentiments raise a host of

questions: Who exactly were these four extremely talented

musicians? If they were so great, was an unfortunate band

name really enough to stop them from making it? And if indeed

they didn't make it, why does anyone still care about them

today? These questions and many more will be answered shortly.

Forget everything you thought you knew about the Kit Kats

- what you are about to read will blow your mind.

John Bradley, a native of Bristol, Pennsylvania, was the son

of musician and entrepreneur Harold Bradley. Harold's shop,

Brad's Music Store, was located on Kensington Avenue in Northeast

Philadelphia, and John could often be found hanging out there.

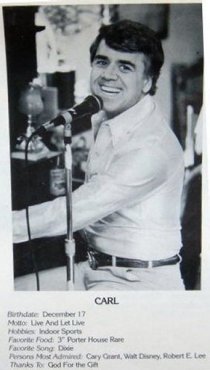

One friend that John made at the music store was Karl Hausman

[1], a young piano prodigy

from Fishtown, a working class riverside neighbourhood in

Northeast Philly. Karl and John were both 13 at the time.

Karl went on to play professionally starting at age 14, while

John honed his guitar chops in a band called the Chancellors.

In the summer of 1958, a 16-year-old Karl joined the Chancellors;

however, John went into the Army the following year and the

band broke up. Karl got a desk job until a rockabilly band

from Ft. Wayne, Indiana asked him for help. Roscoe & the

Green Men were working in the Philadelphia area, needed a

new pianist, and just so happened to hear about Karl. When

he joined this band, he had to adopt a gimmick that was most

unusual at the time. You see, every one of the Green Men had

green hair. [2] Karl toured

with the band for a year; thanks to highly effective representation,

they got to play on The Johnny Cash Show in Canada.

Karl would even stay at their manager's house in Ft. Wayne

whenever the rest of the band went home on breaks. It's remarkable,

then, that the combo spent the entire summer of 1960 in Seaside

Heights, New Jersey, and thus recorded Karl's only single

with them in Philadelphia. This release paired a cover of

'Roll Over Beethoven' with a revival of the mouldy oldie 'Bye

Bye Blues' and came out on the obscure Pontiac label. It was

not enough for Karl, who felt like the group was not moving

"onward and upward" and decided to leave.

WE'RE GONNA BE THE KIT KATS

The year 1961 saw Karl going back to a desk job, miserably

playing the part of responsible young adult like everyone

wanted him to. Everyone but his mother, that is. She encouraged

him to follow his passion for music; luckily, John had just

returned from his term of service and re-formed the Chancellors.

Now 19, Karl re-joined John's band and they played on weekends

in Northeast Philly bars. Enter Carson Wesley Stewart, Jr.

and Ron Cichonski. [3]

In his childhood Carson had earned the nickname Kit Carson,

hence his more common moniker Kit Stewart. Ron, meanwhile,

was not about to explain to every non-Polish rock'n'roll fan

that his last name was pronounced "shi-HEIN-ski",

so he adopted the stage name Ronnie Shane. Kit had learned

to play the drums after getting out of the Navy, and Ron had

a way with a Fender bass. Kit was looking to form a band,

so he and Ron visited Brad's Music Store and asked Harold

Bradley if he knew of a guitar player. Of course, Bradley

recommended his son. When Kit and Ron attended a Chancellors

gig to check out John, Kit was also impressed by Karl's piano

stylings. Kit hadn't considered a piano player, but he had

to invite this great talent to join his new group. As Karl

recalls, "Kit came over to me, he said, 'You know, I'm

starting this group. We're gonna be the Kit Kats.' And I said,

'Hold it right there. I don't like that name.'" The name

was not derived from the candy bar (a UK brand that was not

licensed for the States until 1969), but Karl does remember

that "there were famous Kit Kat clubs around the world"

and concedes that "it worked well with the kids when

the records did come out. The name was, we didn't use the

expression back in [the early '60s], but it was kind of bubblegum."

So why didn't he like it? "I just thought it wasn't macho

enough. It sounded light and airy." [4]

John left the Chancellors to join the Kit Kats, who at this

time also included a sax player named Bob Seeger (note the

spelling!). But Karl was not convinced that he should join

until he saw the new band and was quite surprised by how good

they were. He was particularly impressed by John's singing

voice, which John had kept under wraps in the Chancellors.

So, in February of 1962, Karl joined the Kit Kats. Drawing

upon Kit and Karl's natural strengths, the band established

a division of labour: Kit was the one who sold the band and

did the bookings, whereas Karl was the group's arranger. Also,

the Kats made it a point to respect each other's song choices.

Karl: "We agreed in the beginning, whatever a guy wants

to learn, bring the 45 to rehearsal, and we'll learn it. We

will not argue."

CLUB 13

Through an agent named Herb Lustig, the Kit Kats were able

to start moving beyond the Northeast Philly bars to a downtown

venue named Club 13. They worked there Monday through Saturday

and began to learn what really goes on after hours. Karl has

vivid memories of the weekends at Club 13: "Friday night

and Saturday night, when we were done at 2am, part of our

contract was, we would go upstairs and there was a private

club that started at 2am, and we'd start playing up

there. But there they had some pretty bizarre shows! Like,

we would take a break and on would come a female stripper.

And by the end of her act she takes off her pasties - and

it's a guy! And all of a sudden, we looked at each other -

I thought, 'Hey, I'm from Fishtown, but we didn't have this

sort of thing in Fishtown!' So we had to admit, I was a little

surprised! And the audience was, like, old fat bald guys with

cigars, with young blondes! It was like, all these sugar daddies!"

In the summer of 1962, the group really started to morph into

what we now know as the Kit Kats. For one thing, Bob Seeger

had to be dismissed from the band. It was nothing personal,

but he simply had a hard time tuning his sax to whatever pianos

were available at the venues they played. There were no hard

feelings, and Karl thinks that Seeger went on to become a

lawyer. On July 4th, 1962, the four-piece Kit Kats line-up

made its debut. The last days of summer marked yet another

historic debut by a fabulous foursome: the 4 Seasons with

their first hit, 'Sherry'. The Kit Kats initially encountered

disaster while trying to cover it. Karl sang lead on it originally,

but being a natural baritone without Frankie Valli's amazing

falsetto range didn't help one bit. "I sounded like I

was yodelling," he jokes today. So at rehearsal, Karl

suggested that John sing it. He was amazed by what he heard.

"He sat there and naturally sang in his own voice and

went all the way up," Karl marvels. "I said, 'You're

not even singing falsetto, that's your VOICE!'" In fact,

Karl insists that John's freakish range was totally natural:

"He couldn't go falsetto, he didn't know how!"

Even harder to fathom is that Karl started out giving John

bass vocals - and John was happy to sing them! No more bass

vocals for John; from now on, John would sing tenor or even

soprano, Kit would handle the macho bass and baritone lines,

and Karl would sing baritone or even lay a falsetto on top

of John's high-pitched wailing. With the distinctive characteristics

of each voice, the Kit Kats had some unusual harmonies indeed.

Where was Ron in the vocal mix? "He never showed an interest

in singing," says Karl. "When he did sing, we would

give him bass parts, or if there were songs that would need

a vocal intro, like he would do 'Hee hee hee hee, wipe out!'"

Karl recalls that as the years went by, Ron developed a greater

stage presence in an unlikely manner. "Now, Ronnie DID

sing 'Woolly Bully'. That was his big claim to fame. It got

to the point where the crowd was always yelling for 'Woolly

Bully', just to hear him do his one song! So it was kind of

a joke. Not the joke with Ronnie doing it, it was kind of

the joke with the crowd, you know, 'Bring Ronnie up here!'

'Cause they all called him 'The Wooden Indian' 'cause he stood

there in the back and never moved. When in reality, Ronnie

himself said that he doesn't wear his glasses on stage, and

he didn't wanna step off the stage accidentally! [laughs]

Ronnie was a funny guy. He was quiet, but when he said something,

he was very funny." [5]

It's worth noting that the quiet Ron never committed his vocals

to any of the Kit Kats' records.

VIRTUE

To pick up where we left off, the band began to develop a

following in the local clubs, and in the summer of 1963 they

were playing at Tony Mart's in Somers Point, New Jersey. Who

should be working next door but Philly rock'n'roll legends

the Virtues. Frank Virtue introduced himself to the Kats and

offered them "free" recording time (to be paid for

through record sales, of course) at his studio. The group

accepted his offer and recorded their debut single in short

order. It was an unusual pairing for a rock'n'roll outfit.

The A-side was a rather arch take on the old novelty 'Aba

Daba Honeymoon', which the band hardly ever played live because,

in Karl's words, "It just wasn't rock'n'roll." On

the flip, meanwhile, was the bluesy instrumental jam 'Good

Luck Charlie', which had even more unexpected roots. Karl:

"Basically, we were doing that old ethnic folk song 'Mazel

Tov' and they changed it to 'Good Luck'. That was Frank Virtue's

idea for the title. I think they just threw Charlie on the

end. Charlie seemed to be kind of a popular thing to say back

then. 'Ah, good luck, Charlie.'" That a little rock'n'roll

band out of Northeast Philadelphia (a part of town not known

for its rich musical heritage, though it pains this Northeast

Philly boy to admit that) could offer up such an eclectic

choice of tunes on its first single proves that the Kit Kats

were a cut above the rest. They cast a wide net in building

a repertoire, and they could play anything and make it their

own. In any case, Virtue arranged for the record to be released

on the mighty New York indie Laurie Records, but a positive

review from a San Francisco critic was about as far as it

went.

So the band went back to business as usual, playing the clubs

and recording sundry tracks at Virtue's. Of course, the year

1964 ushered in the British Invasion, of which Karl remembers,

"We loved it because it gave us a chance to play real

rock'n'roll again." There was a bit of a British Invasion

vibe, mixed in with the band's '50s rock'n'roll roots, on

their second single, 'You're No Angel'. Unfortunately, Virtue

got the 45 released on Lawn, the sister label of Philadelphia's

Swan Records. Swan was once one of the biggies, but it was

now in serious decline without Dick Clark in its own backyard

and Frank Slay on its payroll, and (to paraphrase kindly)

Spectropop hero Jerry Ross once suggested that the company's

executives were better suited to selling shoes than records.

Besides, 'You're No Angel' was a tad dated when released in

the context of late 1964. The flip-side was an early recording

of their later favourite 'Cold Walls', with sparse instrumentation

and 4 Seasons-styled harmonies throughout. Both sides were

original compositions, which pointed to yet another division

of labour: when it came to songwriting, Karl composed the

music and Kit wrote the lyrics. For 'Cold Walls', Kit came

up with a haunting tale of a man who was being released from

a lengthy prison stay to the welcoming arms of his love. Speaking

of love, Karl had none whatsoever for this storyline, hence

comments such as, "Even though I wrote the melody for

it, I really didn't appreciate it until I recorded it myself

instrumentally. And then I listened to it and I thought, 'This

is an absolutely beautiful song!'"

JAMIE

The failure of the second single must have caused frustration

for the Kit Kats, and Karl started pushing for the band to

go to California, believing that the Golden State would be

a better launching pad to stardom. [6]

Kit couldn't work out any deals for the summer of 1965, but

thought that he might be able to set something up for the

winter of '65-'66. Then fate intervened. And fate's name was

Bob Finiz. Finiz had been the boss bass voice of Philly doo-wop

favourites the Four J's, and he was now a staff producer and

engineer at Jamie Records. Jamie was part of a large Philly

music empire owned by attorney Harold B. Lipsius. [7]

His domain included the Jamie/Guyden family of labels, plus

local and national record distributors. Artists like Duane

Eddy and Barbara Lynn, and producers such as Phil Spector,

Lee Hazlewood and Huey P. Meaux had all gotten a huge boost

from recording for, or partnering with, Lipsius. By 1965,

Jamie/Guyden was poised to become the only Philly indie from

the 1950s to successfully survive the onslaught of the British

Invasion and the concurrent rise of the Motown hit machine.

In other words, being noticed by somebody from one of Lipsius'

companies was a big deal.

THE T-BAR

Finiz approached the Kats at The T-Bar, one of their favourite

venues, which was located in Ridley Township, Pennsylvania.

After talking some business with them, he told Lipsius about

this great band he'd seen, at which point Lipsius asked to

hear them on tape. So Finiz returned to The T-Bar and took

the Kats to Jamie's in-house studio after their set was over.

Karl recalls, "I didn't need to take the piano, but he

wanted me to take the amplifiers anyway. That's why the piano

sounds a little tinny on the recordings, because he wanted

it through [the amplifier] like that. And the only reason

I made it tinny was to cut through the guitar. If I'd had

a natural piano sound, you'd have never heard me." And

what kind of amplifier did Karl use? A ukulele pick-up, of

course! It was a trick that he'd learned from Robbie Robertson

of the Hawks (later the Band), whom he'd seen in Toronto when

he was a Green Man, and at Tony Mart's in 1965.

As you know by now, Harold Lipsius was pleased with what he

heard and signed the band. Technically, though, the Kit Kats

were still under contract to Frank Virtue. Lipsius, ever the

skilful businessman, took care of that. Not that the band

didn't like Virtue - as Karl remembers, "He was a quiet

fellow, but very polite, very nice" - but they rightly

believed that Jamie could do more for them. Jamie assigned

Bob Finiz to produce the foursome, and this is where Tom Kennedy

sees a major problem. Kennedy feels that Finiz was better

off producing R&B acts because of his roots in doo-wop.

Kennedy also finds it detrimental that Finiz was left to fly

solo with the Kats, as opposed to his collaborative work on

other artists' recordings (for example, he was under the influence

of Gilda Woods when he produced Brenda & the Tabulations).

Letting his imagination run wild for a moment, Kennedy fantasizes

about what great work Tom Dowd could have done for the Kats,

asserts that Felix Pappalardi would have "torn a new

asshole" with them, and proclaims, "If Koppelman

and Rubin had done the Kit Kats, they would've been the Turtles."

Remember that last one.

Maybe they could have done better than Finiz, but it's hard

to argue with the crash-boom-bang of the Kit Kats' first Jamie

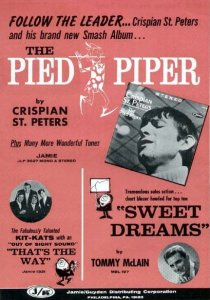

release, 'That's The Way'. Following, of all things, Crispian

St. Peter's 'Pied Piper' in the Jamie singles catalogue, 'That's

The Way' was retro-chic before the concept was in vogue. The

doo-wop influenced vocals and Jerry Lee Lewis-styled piano

kept the boys grounded in '50s rock'n'roll, but Kit's lyrics

betrayed something that is not normally associated with this

band: a punk attitude. "You'd like to hear me say I'd

change my ways for you/I wouldn't change for anyone, things

I like to do! […] That's the way I'm gonna stay, nothing

will change me!" As they modulated almost incessantly

on the final choruses, they displayed a maturing musicianship

that set them apart from most local combos of that or any

other era, while the production included elements that were

distinctly mid-'60s. The Spectorian echo employed by Finiz

gave the record, in Karl's opinion, the feel of an early Sonny

& Cher track, while Finiz also decided to throw in a harpsichord

for a baroque pop feel. [8]

On the flip-side was a rough recording of what would become

the band's signature tune, 'Won't Find Better Than Me', sounding

as close to garage rock as the Kats ever got during their

Jamie days, but still keeping a classical element in Karl's

fast-fingered piano solo. [9]

In all, it was a highly impressive offering, and it paid off.

The record was a hit in Philadelphia and all along the Jersey

shore. Karl also remembers DJ Chuck Raymond of WLAN in Lancaster,

Pennsylvania reporting to the band that 'That's The Way' hit

#1 on that station's survey [10]

and on a pirate radio ship in London!

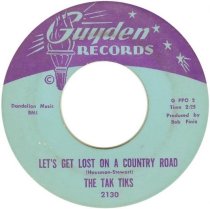

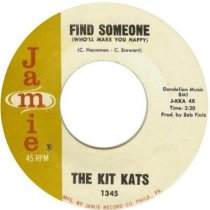

With such a rockin' Jamie debut, the record-buying public

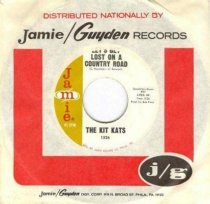

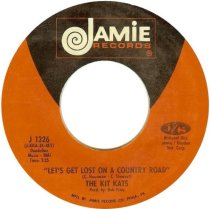

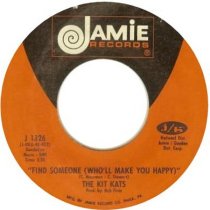

might have been surprised to hear the sweet, romantic follow-up

'Let's Get Lost On A Country Road' (backed by the swinging

'Find Someone'). Its unconventional melody and arrangement

were inspired by Aaron Copland, one of Karl's favourite composers.

For the solo, John plucked away at a banjo, an instrument

he'd often played when the Kats did their Mummers Medley on

stage. [11] Otherwise,

the record had a full-blown baroque pop production, complete

with strings and horns arranged by Richard Rome. "What

a nice guy," enthuses Karl. "He would sit right

there on the piano bench with me and ask me to play the song

and he would be writing away, putting down the notes that

I was playing, and then he would come back a few days later

with the entire string arrangement." The orchestration

was overdubbed after the Kats laid down all their parts, and

though Karl did not think the additional instrumentation was

necessary, he liked the way it sounded. Nevertheless, the

poppy sound of 'Country Road' indicated a growing disconnect

between the live Kit Kats and the studio Kit Kats. "I

didn't really write driving rock'n'roll melodies," Karl

admits. "We couldn't duplicate what we really sounded

like on stage 'cause we didn't write that kind of music."

Nobody seemed to care. 'Let's Get Lost On A Country Road'

was a big hit in several East Coast markets, Philadelphia

being the biggest of them all. Its regional success allowed

it to make the Billboard charts, although it only "Bubbled

Under" the Hot 100 at #119. [12]

With 'Country Road' riding many regional hit parades, Tom

Kennedy had an idea that he'd just as soon forget: releasing

an instrumental version of 'Country Road' under a pseudonym.

Why? "Because it was such a diversion from what the band

was doing," he explains. "It was really a novelty

approach. I think I heard Karl doing that in the studio and

I thought, 'God, that isn't a pop song, but it IS a novelty

song. It's like a Crazy Otto. That's a different kind of piano,

and if we're gonna do it, let's not put the band in jeopardy.'

I mean, who did I think I was? The 4 Seasons calling themselves

the Wonder Who? But I just felt, you know, we don't wanna

be hamstrung into this sound, and it's too diverse from what

they're doing, it doesn't make sense. We'll put another record

out and we'll just change the name." As it was, the instrumental

'Country Road' had two rides under two different pseudonyms,

and the first time around it was the B-side of a Ramsey Lewis-inspired

workout of 'Hanky Panky'. With regards to Tommy James' then-recent

chart-topping version, Karl recalls, "I liked playing

the instrumental version. I didn't like the hit version because

of the vocal." This single was released in late 1966

under the name the Pablo Ponce Four, a nom de disque

the origins of which are murky; it was definitely chosen around

the time of the recording. 1967 saw a re-release of the instrumental

'Country Road' on the A-side of a 45 bearing the name the

Tak Tiks. Tom Kennedy takes the blame for that one, adding

amidst a sea of laughter, "Now, was that about as clever

a way to disguise the name as you possibly could come up with?"

To add an extra layer of mystery to the proceedings, both

instrumental singles were issued on Guyden. The Tak Tiks'

version of 'Country Road' did reasonably well in Philadelphia.

Returning to our normal sequence of events, the band's third

Jamie single, 'You've Got To Know', came out in February of

1967, and Karl remembers its success being quite limited:

"42 cities in Florida, it was a hit. And nowheres else.

We talked to vacationers who had come back from Florida. Bands

were playing it on the beaches of, like, Daytona, Ft. Lauderdale."

It was a fast soul-influenced dancer, but the finished product

was a bit problematic from Karl's point of view. "I thought,

'It's too goddamn fast!!! How the hell could we have recorded

it that fast??? It was supposed to be slower!!!' I said, 'Karl,

because artists have that problem. You get carried away with

your enthusiasm, the beat goes faster! No one had any idea

what tempo you wanted it!'" Unfortunately, that wasn't

the only thing that was wrong with it. While in keeping with

Kit's growing tendency to write didactic lyrics, lines like

"You've got to know when to give in/You've got to know

when patience is thin," "Every boy should have a

girl who'll see him through," and "There are things

that you must do/If you want to keep him […] And you

know you'll need him, girl" might have come off to members

of the burgeoning Women's Liberation Movement as a clarion

call to all females to be servile to their men. Certainly,

the song hasn't aged well and doesn't stand a snowflake's

chance in Texas of being well-received in the era of political

correctness. In response to these criticisms, Karl muses,

"I'm glad I didn't pick up on that, we'd have had a hell

of a fight. Because I always loved independent women."

So what good can be said about 'You've Got To Know'? Karl

is convinced that it inspired the melody of the Dells' 1968

hit, 'There Is', but doesn't mind that because he liked 'There

Is'. Riding on the flip of 'You've Got To Know' was an altogether

more promising side, an extremely baroque re-recording of

'Cold Walls', adding Richard Rome's orchestration and de-emphasizing

the harmonies. [13]

THE RIPTIDE

The Kit Kats were proving themselves to be a big group on

the East Coast, which led to a rather attractive offer from

one John Caterina. Caterina owned a 1,600-seat nightclub in

Wildwood, New Jersey called The Riptide; as you may have guessed

from Bobby Rydell's 'Wildwood Days', the South Jersey resort

town was successfully marketed to Philadelphians as an attractive

oceanside summer getaway. But Caterina was not pleased with

his club's performance and was looking to improve his fortunes.

In March of '67, he offered to make the Kats summer regulars

at The Riptide, in exchange for which they would receive a

40 percent cut of the club's profits. [14]

They couldn't turn that down, so from Memorial Day to Labor

Day they worked The Riptide seven nights a week plus two jam

sessions on Saturdays and Sundays. This started in 1967 and

continued through 1970, after which Caterina sold the club.

With Caterina went the Kit Kats' deal, but they sure packed

the place during those four years they were there.

May, 1967 brought a new single, 'Breezy', which suffered from

bad timing - and bad titling. How could Jamie have known that

the Association's 'Windy' was being released at the exact

same time? 'Breezy' failed to become a hit anywhere, but with

its French-influenced melody (and accordion solo by Karl)

and breathy vocals it showed a softer, gentler side that made

'Country Road' sound positively bombastic by comparison. It

was also Kit's favourite Kit Kats tune. For the first time,

Jamie sent the band out of town to record it, which they did

at Bell Sound in New York. The flip was a tighter re-recording

of 'Won't Find Better Than Me', which appeared on some radio

station surveys [15],

while aggravating fans who did not want to see a song they

already owned being recycled on the B-side.

IT'S JUST A MATTER OF TIME

It was about time to put together an album, and its title

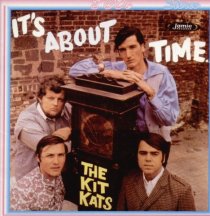

It's Just A Matter Of Time was Tom Kennedy's expression

of faith that the Kit Kats would soon become national stars.

The rather unattractive front cover was credited to Kennedy

and Max Bodden, but it is the latter who must shoulder most

of the blame. Kennedy: "Max was the art director for

Jamie/Guyden, Phil-LA of Soul. He actually did our graphics

and the artwork. I couldn't deliver a picture, I could only

deliver an idea. I felt that they were just on the brink of

making it, and it was a matter of time. And Max said, 'Well,

look, why don't we put 'em around a grandfather clock?' And

I said, 'That'll work.'" Kennedy reveals that the cover

photo, featuring the guys gathered around a beaten-up clock

with pissed-off expressions on their faces, was Bodden's idea.

It's still a sore subject with Karl, as he groans at the very

mention of it and exclaims, "I, uh, [laughs] I

didn't like it! I remember the morning we went out there,

it was a chilly morning. We went down around 2nd and Fairmount

and found a vacant lot that was junky lookin' and somebody

was there, Bob Finiz was there, somebody showed up with a

grandfather clock!" [laughs] His next statements

are quite telling: "They DID take some nice pictures!

I liked the pictures where we smiled, you know, we looked

great. We looked like the band was, we made people feel good.

They picked the one that looked like we just went to our own

funeral! We weren't that kind of band to say, like, we're

bad!" There's a certain innocence to these comments

that stands in stark contrast to the angst-filled cover shot.

Indeed, the Kit Kats faced a problem that all good-time bands

were forced to confront in the mid-to-late '60s. The times

had become more turbulent, and rock music's trendsetters were

no longer content to purvey songs that served as an escape

from life's problems. As audiences responded to these artists'

opuses of frustration, alienation, and disgust, they also

found comfort in the rough and tumble bands whose "bad"

attitudes reflected most listeners' inner turmoil. But the

Kit Kats weren't interested in that. All they wanted to do

was have fun and get you to have fun with them. They didn't

even do heavy drugs because, as Karl himself will gladly attest,

they were turned off by the effects such substances had on

others. A music act that wanted to be so happy and clean-cut

could have found a niche in the world of bubblegum, but the

name the Kit Kats is as close to bubblegum as that band got.

So where exactly did the Kit Kats fit in? On the Philly scene,

this was not as much of a concern; after all, pure doo-wop

records were still becoming local hits, and edgier styles

like garage rock and psychedelia were mostly imported from

other cities. But as Tom Kennedy pointed out, Jamie held high

hopes of breaking the Kit Kats nationally with It's Just

A Matter Of Time. It's likely that Max Bodden was painfully

aware of the Kit Kats' potential for image problems on a national

scale; why else would he have chosen such an ugly cover photo

to depict a band that made such beautiful music?

Indeed, the music contained on the album was much more appealing

than the packaging. Aside from all the Jamie A and B-sides

(save for the 'Country Road' flip, 'Find Someone', and the

original 'Won't Find Better'), there was a mind-bogglingly

eclectic selection of covers, all of which came out sounding

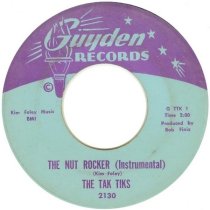

like no one but the Kit Kats. 'Nut Rocker' (a complete feature

on which can be found elsewhere at Spectropop) was the band's

set opener for many years, and it would also be used as the

B-side of the Tak Tiks single later in 1967. [16]

The folk tunes 'Cotton Fields' [17]

and 'Liza Jane' got rocked up; Karl picked up the latter from

Ronnie Hawkins & the Hawks. It was a real barnburner which

the Kit Kats used as a set closer when Karl got tired of ending

with 'Goodnight, Sweetheart, Goodnight'. Tom Kennedy remembers

how powerful their live version was: "[Karl would] bang

the shit outta the piano and John would sing it in the key

of Q! And the place would shake for 3 minutes after they stopped

playing." Karl agrees with Kennedy that the recording

was missing one essential element: the crowd! Karl had also

picked up a 45 of the Ivy League's 'Funny How Love Can Be'

and presented it to his bandmates as a possible cover choice.

Their rendition is breathtaking, especially with the band's

full harmonies and Richard Rome's orchestration, but since

the original version had not been a hit in the US, people

thought the Kit Kats had written it. 'These Are A Few Of My

Favorite Things' was the strangest inclusion, but it was a

staple of the band's opening sets, when they played non-rock

while people drank and started rocking when people were ready

to dance. Karl believed it would work for the Kats: "I

said to the guys one day, 'Why don't we do something like

show tunes? We're not Broadway guys, but we could certainly

do something classy.' So I happened to come upon that one

and I said, 'This would be great with three-part harmony.'"

Bob Finiz considered it worth including on the album to show

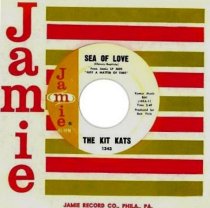

the group's versatility, and that it does. 'Sea Of Love' was

an obvious choice for a band whose roots were in '50s rock'n'roll,

but their unique arrangement of it came about through a gradual

evolution. They had been performing it since the beginning

of the group, but after a few years Karl decided it needed

embellishment. They started jamming on it, and one time Karl

asked Kit for a drum reprise at the end, after which Karl

let loose with a piano solo and the others fell in. Add some

higher-than-high harmonies and a few light orchestral touches

and you have the most distinctive version of this oft-covered

chestnut ever recorded. (A September single release, which

faded early on Karl's piano solo, would muster up enough regional

success to hit #130 on Billboard, and a Canadian

pressing on the Apex label did quite well north of the 49th

parallel.)

It's Just A Matter Of Time came out during the Summer

of Love in a reverb-drenched mono edition and a "stereo"

pressing that was entirely re-channelled. The back cover identified

John as Big John, the nickname he had earned due to the changes

wrought upon his body by too much of la dolce vita,

while Karl, who had never requested an arranger's credit,

was surprised and flattered to receive one anyway. Like most

'60s albums, It's Just A Matter Of Time contained liner

notes full of endless praise, bragging, and a little hyperbole

for good measure. Quotes from deejays, program directors,

and distributors all over the East Coast made the Kit Kats

sound hotter than a bunch of jalapenos. "[S]ales of 37,000

records of 'Country Road' in Philadelphia alone was proof

enough that this group is where it is," wrote Jim Hilliard

of Philadelphia's famed WFIL. Dean Tyler of 'FIL rival WIBG

(a.k.a. Wibbage) gushed, "[T]hey happen to be four of

the nicest guys it has ever been my pleasure to meet in 16

years in radio and TV." [18]

Kerby Scott of WBAL in Baltimore even offered a stern warning

to the Beach Boys: "The Kit Kats are one of the few groups

with enough talent and showmanship to bring the scene back

to the East Coast - California beware!" Not surprisingly,

It's Just A Matter Of Time didn't exactly become the

next Pet Sounds. It did hold its own in the Philadelphia

area, however, where Karl claims it sold over 80,000 copies.

THE VIRTUE ALBUM

It's Just Matter Of Time may have had to go up against

Sgt. Pepper that summer, but in the fall it had a much

more immediate competitor. Frank Virtue gathered up 'You're

No Angel' plus 11 outtakes from 1963-64 and released them

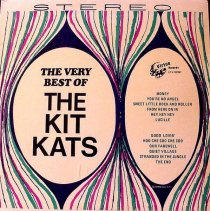

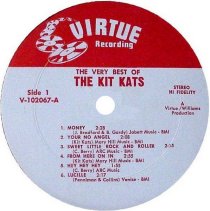

on his own label under the deceptive title The Very Best

Of The Kit Kats. Much of the album suggests that the Kats

were originally R&B-oriented, though Karl admits that

"it just turned out that way, although we didn't have

R&B voices. Our voices were simply too - we weren't gravely

enough." Still, their rockin' renditions of Little Richard's

'Hey Hey Hey Hey' and 'Lucille' and the old Chubby Checker

hit 'Good Good Lovin'' showed that they did have an understanding

of rhythm and blues. They also cut an R&B-styled take

on 'The Quiet Village', which featured the band making intentionally

goofy bird call noises. The Virtue-penned instrumental 'The

End' also brings in an R&B stomp, while their faux Merseybeat

reworking of 'Stranded In The Jungle' sounds like a lost You

Know Who Group recording. The band used to put on shows during

their sets, hence the English accents and banter on 'Stranded',

but Karl feels that it didn't quite come off on the record.

The original material on the album indicated something different

altogether. The unusually sombre, pensive 'Our Farewell' was

firmly in the white doo-wop tradition - complete with Karl's

melodramatic spoken passages - while 'From Here On In' comes

closest to indicating the retro-contemporary direction the

Kats would take at Jamie. Nevertheless, the Kats were embarrassed

by the raw, primitive recordings on the Virtue LP and asked

Virtue to pull it. Having no reason to do so, he didn't, and

the band could only watch helplessly as fans purchased an

album that siphoned sales away from their Jamie output. [19]

Around this time, Bob Finiz disappeared to California, leaving

the Kit Kats without a producer. That wasn't the only change

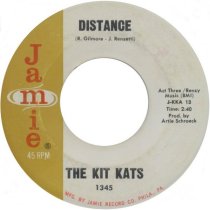

in store for the band's next 45; 'Distance' was the first

single not written by Kit and Karl since 'Aba Daba Honeymoon'.

The song had been cut by Spanky & Our Gang on the B-side

of 'Sunday Will Never Be The Same', and it had some important

Philly connections. For one thing, it was written by prolific

arranger/composer/musician Joe Renzetti and the Spokemen's

Ray Gilmore, who was also a DJ on Wibbage. Additionally, Spanky's

version had been produced by Jerry Ross. Karl says this cover

choice "was more or less set up with Kit talking to Jamie"

and that the Kats didn't really appreciate the song until

they learned it. Jamie sent them to New York to record it

with Renzetti doing the arrangement and Artie Shroeck producing.

Karl has vivid memories of the demanding Shroeck: "He

was a taskmaster, but he made sure that when it was over and

done with, we were glad he did. What he did was get out of

you what you didn't know you had. And that was the interesting

part about it. You understood when it was all over."

Karl was not aware of Shroeck's impressive résumé

(including arrangements for one of the Kit Kats' favourite

bands, the 4 Seasons) until after the fact: "He was not

a braggart, just a regular person. Which impressed me even

more! I liked that." The winning combination of Shroeck,

Renzetti, and the Kit Kats made for an excellent piece of

ragtime sunshine pop, with John's chugging guitar, Kit's swinging

drums and a thick wall of background harmonies; it was a much

livelier reading than Spanky & Our Gang's languid, morose

rendition, but John's lead vocal retained an appropriate amount

of pathos and anger for the lyrics. Also, Shroeck's production

included the only backwards tape effect ever to be found on

a Kit Kats record. Unfortunately, the single failed to catch

on anywhere.

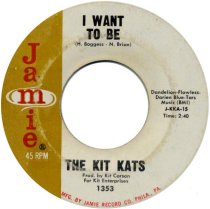

As 1967 turned into 1968, the band nearly came apart at the

seams. Kit, the businessman of the band, was becoming somewhat

more ambitious. On the plus side, he produced the Cole Brothers,

the Kit Kats' alternate band down the shore, for Jamie Records.

[20] On the minus side,

he got the idea to record John with session musicians - a

means of pushing John as a star vocalist - while still crediting

these records to the Kit Kats. This led to such highly unrepresentative

singles as a heavily orchestrated cover of Neil Diamond's

'I Got The Feelin' (Oh No, No)', a silly piece of piffle entitled

'I Want To Be', and the cheery Cowsills-like 'Hey Saturday

Noon'. [21] None of these

singles made a commercial impact, and Tom Kennedy offers a

good explanation why: "You would never have to take any

one of [the Kit Kats] off the session to make it sound right,

no matter who was producing it. There were concessions to,

you know, 'If we spend more money on musicians, maybe we'll

get a better sound.' And it wasn't terribly expensive, but

it was a roll of the dice, and I think it just proved a point

that augmenting them with studio musicians wasn't going to

improve their sound that much if they weren't the nucleus

of what was happening."

There were two 1968 sides on which the Kats were the

nucleus of what was happening. Their swinging, mildly funky

reworking of the Beach Boys' 'You're So Good To Me' was an

obvious choice to record. As Spectropop's own Steve Harvey

(not to be confused with the famous comedian) once recalled,

"Kit Stewart told me they used to do that as a stomper,

it was a real 'smack your feet into the floor of the club'-type

tune." Karl got his arranger's credit on the single,

but he was annoyed to see Kit credited as producer. "I

said, 'Kit - where do you get producing? You came in as a

studio musician same as we did.' He said, 'Well, you know,

it was my idea to do the song.' I said, 'Why don't you have,

'Based upon an idea by Kit Stewart?' You didn't produce this

- the band produced it!'" Karl has much fonder memories

of the mixing process: "I remember when it was being

mixed, and I said [to engineer Joel Fein], 'Do me a favour.

Everything we have ever recorded sounds like it has no bass

in it. Can you turn that knob up a little higher?' And he

said, '[forebodingly] You're gonna push it into the

red.' And I said, 'Put it into the fucking red! Please turn

that knob!' And he said, 'Okay.' And you know it's the one

song [we] recorded that actually has balls!" Maybe so,

but the commercial success of 'You're So Good To Me' was confined

to the Jersey shore - not enough to make it sell notably.

[22]

The flip-side was a source of great resentment between Karl

and Kit. Donnie Owens' 'Need You' had been one of the few

hits for the Guyden label back in 1958, and it was a favourite

of Karl's. Of all the live numbers that featured his lead

vocals, 'Need You' got the most requests. It was a no-brainer

to record, but when Karl heard Kit's florid production of

the finished product, he was furious: "I wanted it to

be like the Donnie Owens original version. Simple acoustical

guitar, me singing it, brushes on the drums, and light bass.

And I said, 'That's all, that's all.' And I said, 'You give

me these frickin' strings, all this kinda crap you put the

hell in there,' and he said, 'Well, you know, I wanted to

fatten it up.' I said, 'Who the hell died and [made] you boss?

I did the arrangements in this band and it did pretty goddamn

good! You were the one that sold the band, but I gave you

one hell of a product to sell. All of a sudden you decide

that you're Mr. Producer!'" For what it's worth, Kit

finally admitted that he had indeed ruined 'Need You' …

a mere 32 years later.

FINIZ RETURNS

It wasn't just internal tension that threatened the band's

well-being. 1968 saw the return of Bob Finiz, who sued the

Kit Kats for not paying him as their manager. Never mind the

fact that Finiz didn't manage the Kats; they still

had a percentage of their salaries held in escrow until the

matter was settled. That is, if you can consider the

matter settled. Karl picks up the story from here: "The

bottom line on the thing was, we all go to court and Bob Finiz

WINS! He wins, but get this - we not only didn't get our money

back, HE didn't get any money back, it got locked up between

the judge and the lawyers! And that's what Bob Finiz said,

because we said, 'You son of a bitch, how the hell could you

do something like that?!?!' He said, 'Well, guys I really

didn't wanna do it, but I was told I was within my rights.'

I said, 'You had no rights! You were no manager! You were

with the recording end, but you CERTAINLY didn't manage us!'"

With the hard feelings long over, Karl now maintains that

Finiz was put up to suing the band, though he doesn't know

who put Finiz up to it. [23]

Even amid such turmoil, the Kit Kats continued to be a huge

draw in person. Their set list was always eclectic, with such

crowd favourites as 'Malaguena', '500 Miles', the 4 Seasons

Medley and a host of Motown hits. (In later years, performances

of Abbey Road and Tommy were real crowd pleasers

as well.) Big John, the only non-smoker in the band, proved

to have amazing stamina, never finding the high notes a challenge

unless he had a cold. Tom Kennedy is still dazzled by the

memory of their live shows: "People hated to hear the

last song. They just got on stage and perennially cooked through

the whole set. They were dynamite in person, and the amazing

thing was, if Finiz was getting something on the records that

sounded big - they were getting it in person. Their sound

in person was probably as good as, if not better than, their

recordings. I don't think [the recordings] could capture the

fullness of the band." Kennedy also remembers how, in

a matter of seconds, the Kats were always ready to rock'n'roll:

"There were a lot of bands that, when they came on, they

spent an eternity tuning up, soundchecking … it was annoying.

In my eyes, it was very unprofessional. When the Kit Kats

came on stage - I don't know if they waited out in the parking

lot and tuned everything up - but they got on and in a

minute they were ready to play and they were right on."

The band always took great pride in developing a personal

rapport with their fans, especially with Big John walking

out into the crowd and greeting people or joking with the

audience from the stage. As Kennedy recalls, "You know,

they had such a following, it was almost like a first-name

basis. John would point - 'Johnny, welcome!' - you know, and

he'd point to a guy. I mean, it was a following and

they were very connected with their audience." So popular

were the Kit Kats in person that they even found themselves

becoming the subjects of tributes. Karl: "There was a

group who used to play in the Philadelphia/Jersey/Jersey Shore

area called Jimmy & the Tropics. They would do a whole

Kit Kats medley. Matter of fact, they're still together. They

would warm up or play during our breaks, or we would alternate

with them, anyway you wanna put it, if the place would have

two bands. They actually surprised us one night. They said,

'Would you stick around and listen to our set?' And they did

the Kit Kats Medley and they had been doing it for quite a

while. I just couldn't get over it. I felt embarrassed, I

felt like, 'Why would you want to do that?'"

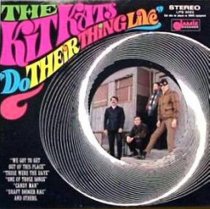

DO THEIR THING LIVE

It made sense, then, that the Kats' next record - indeed their

only release for most of 1969 - was a live album. The Kit

Kats Do Their Thing Live was recorded in November 1968

at The T-Bar, and featured none of the group's hits. Instead,

it contained an incredibly diverse list of covers, from the

Roy Orbison hit 'Candy Man' (featuring Karl on harmonica)

and the Mamas & the Papas' 'Words Of Love' to 'Great Balls

Of Fire', 'We Gotta Get Out Of This Place', 'Little Queenie',

'Those Were The Days' and an almost psychedelic reading of

'Distance' (prominently featuring the Rock-Si-Chord, an electric

keyboard that Karl set up on top of the piano). The inclusion

of Phil Ochs' 'Draft Dodger Rag' showed the band incorporating

topical songs into their repertoire, but don't think the Kats

were suddenly getting political: "It was just the times,"

explains Karl. "We never discussed politics. We never

knew how each other voted or anything like that. I don't even

know if the other guys even voted!" [24]

The live album may have captured the group's versatility,

but the sound quality was nothing to cheer about - even though

it was true stereo. "It was so much treble,"

moans Karl. "It sounded so tinny that it was actually

horrible. I think what they did was actually record it just

the way it was, but there was no bass in there. The piano

sounded like a harpsichord on that album!" Furthermore,

the back cover made the stupid mistake of claiming that The

T-Bar was located in Broomall, Pennsylvania, a factual error

that has muddied the band's history ever since. Nonetheless,

the album sold very well in the Philadelphia area and down

the shore upon its release in early 1969.

NEW HOPE

A fortunate turn of events for Jamie also proved pivotal for

the Kit Kats that year. Jamie/Guyden picked up a small Florida

label, Sundi, whose release of Mercy's 'Love (Can Make You

Happy)' was burning up the charts in the Sunshine State. With

Jamie's distribution, the record became a national smash in

the spring and summer. One of its producers was the eccentric

Mike Apsey, who convinced Harold Lipsius to hire him to work

for Jamie. He became the Kit Kats' new producer, although

it was not quite as cosy an arrangement as the band had once

enjoyed with Bob Finiz. Whereas Finiz attended the band's

shows frequently, Apsey was only an occasional spectator.

The Kats had socialized with Finiz, while their relationship

with Apsey was more businesslike. Apsey seems to have been

more interested in Karl than the rest of the group; he would

call Karl into the studio to add background parts or smooth

out rough edges after the foursome had laid down their tracks.

Nonetheless, the producer had one hell of a trick up his sleeve:

recording yet another version of 'Won't Find Better Than Me'

to be released undoubtedly as an A-side. Karl came up with

a gorgeous new arrangement, placed firmly in the soft rock

vein but with all the elements of the Kit Kats' sound: powerful

drumming, country-rock guitar work, lively bass, and classical

piano. A slight Latin tinge made the record all the more distinctive.

The band's signature harmonies were as strong as ever, but

Karl reveals that he played a bigger role in them than usual:

"On 'Won't Find Better Than Me', I'm the only one doing

background. We eliminated the three-part harmony that was

on there, and I think I said, with no - you know, not cutting

out the other guys - but I said, 'Bottom line is, we want

it to sound better.' And so what I did was just work with

Mike, and I just kept doing vocals in layers ... 3 of my own

voices, and that's it. And it worked out fine." Since

the song had already been out twice under the Kit Kats name,

Apsey (credited as Mike for some reason) thought that a new

name was in order. New Hope, Pennsylvania was (and is) a small

town known for its tourist-baiting arts scene; thus Apsey

chose to rename the band the New Hope, which was later shortened

to New Hope. Karl was happy to lose the Kit Kats moniker,

but he didn't think New Hope was much of an improvement: "I

said, 'Mike, you have to look at it as a cynical Philadelphian.

People are gonna call us No Hope!' And sure enough, we did

[veteran Philly deejay Ed Hurst's afternoon dance show]. So

one day he introduced us as New Hope and he said, 'Oh! I almost

said No Hope.' I said, 'Son of a bitch, I was right!'"

Fortunately, the band lived up to the name New Hope, not No

Hope. The new 'Won't Find Better' was released at the end

of 1969 and, in the biggest development yet in the group's

lifetime, made Billboard's Hot 100 in January of 1970.

It peaked at #57 in a nine-week chart run, but it was a much

bigger hit in many cities across America. Why did this record

do so much better than anything before it? Karl's answer is

simple: "I think it sounded good." At any rate,

Jamie rewarded the guys by sending them on all-expenses paid

trips to the record's biggest cities whenever the band was

available. It's worth noting that at the clubs back home,

the group stuck with the name the Kit Kats because it was

still a draw under that name.

The next New Hope single came in April, and it was a peculiar

offering. 'Rain' was a catchy tune from outside writers, but

its soft rock sound was a tad too sweet and polished; not

surprisingly, the instrumental tracks were cut with session

players. John, Kit (who takes the lead on the bridge), and

Karl were the only Kit Kats on this record, and their contributions

were strictly vocal. Even though it followed a hit single,

'Rain' failed to make a splash. Oddly, the B-side was 'Let's

Get Lost On A Country Road' with horn overdubs, showing that

Mike had a somewhat unhealthy obsession with the Kit Kats'

oldies. Karl remembers that Mike "liked our old material

and wanted to do 'em over again. And even I said, 'Why? Kit's

got songs, I've got songs … we've got a whole bunch of

new stuff'… but somehow they felt like they should [laughs]

just take our old songs, basically, and take some of the echo

off. And that was it! And then of course we re-recorded some

of the songs."

TO UNDERSTAND IS TO LOVE

These bizarre ideas led to a mess of an album. To Understand

Is To Love (commonly referred to as The New Hope LP)

was released in August to undeservedly good sales. The album

was a pathetic mishmosh that was never quite what it seemed

to be. Apsey had Karl record a long piano-and-harmonica intro

for 'Won't Find' and tacked it onto the main track; somebody

(perhaps Kit) also added an unnecessary tambourine overdub.

'Gregorian' was simply the first verse of 'Won't Find' sung

like a group of monks; it was intended as a joke but even

Karl found it embarrassing. 'You're So Good To Me' was included

in a weak stereo mix that surgically removed the 45 version's

"balls", while Apsey presented 'Distance' in stereo

with the first half of the intro lopped off. 'Country Road'

appeared with the original mono 45 master drowned in obtrusive

stereo horn overdubs, while 'Breezy' was resurrected in mono

with some stereo elevator music thrown on at the beginning.

The guys re-recorded 'You've Got To Know' in a deliberate

tempo meant to rectify the excessive speed of the original,

but the new version lacked the original's fire. 'Find Someone'

also got a needless makeover, with smoother but less interesting

harmonies and an instrumental tag that segued awkwardly into

'They Call It Love', the dull soft popper that had occupied

the B-side of the first New Hope single. [25]

The ridiculous 'Won't Find Better Than Me Medley' was not

even supposed to be released, nor did it take shape as originally

planned. Karl had the idea to do 'Won't Find' in the styles

of various '50s artists, with each singing Kat taking his

turn on lead. However, Apsey insisted that he had to leave

town and rushed the band to finish the album; thus, Karl sang

all the 'Won't Find' segments and Apsey broke them up with

snippets of the Kit Kats' covers of 'Need You' and Bertha

Tillman's 'Oh My Angel'. [26]

Karl's memories of this artistic misfire are understandably

bitter: "It wasn't supposed to happen. It was just something

I came up with and thought it'd be fun to do for the hell

of it, I think for our own enjoyment. Give the guys each a

copy and send us home. And he stuck it in the album and I

thought, 'Nobody's gonna understand this! It makes no sense!'"

With 'Rain' also on board, the album was starting to look

like a loser. Fortunately, the fantastic foursome provided

two new originals that showed promise - even if they were

both rather extreme departures from the Kit Kats' formula

of churning out goodtime pop tunes with traditional boy-girl

storylines. 'Look Away' was a long, progressive pop opus with

extended instrumental passages and choir-like vocals. Kit's

lyrics were so obsessively preachy that they bordered on nitpicking:

"People talking everyday, but ask them what they want/Speak

their minds in every way, but never lift a thumb/Always want

to have their say, but saying's all they want." But the

point that some people talk a great talk and never actually

do anything was a good one, and the musical experimentation

was really the main attraction of the recording. Karl's vibrant

piano and accordion solos ('Won't Find Better Than Me' is

in there somewhere) were complemented by some very cool bagpipes,

which came about because Karl wanted to go for a Scottish

marching band feel. To achieve this end, Jamie hired Rufus

Harley, master of the jazz bagpipes. [27]

Karl has fond memories of the off-the-wall jazzman: "I

remember, he comes down - a really elegant guy, you know,

and he had one of these Yemen-type caps on, and he goes into

the office and he says, 'Yeah, I'll do the session! I got

my bagpipes with me … I want 400 dollars.' Jamie says,

'Will you take 100?' He said, 'Sure!' So that was a quick

settlement! So he comes upstairs and he said, 'Uh-huh! Glad

to be workin' with you guys!' And we said, 'Oh, we're honoured

you're here!' And the funny thing, he really just made us

laugh when he opens up the case, takes out the bagpipes and

says, 'We'll be in business soon as I blow these motherfuckers

up!' [laughs] So anyway, he did, and he played right

along with us, and we had a fun afternoon with the guy."

Fun was not in order for the other new selection, 'The Money

Game'. Though rock critic Richie Unterberger resists no opportunity

to compare this track to the Easybeats, it was actually inspired

by the Beatles. Karl had composed a soft and lilting melody

a la 'Martha My Dear', but Kit's lyrics were unexpectedly

hard-hitting: "All the things that I've been thinkin',

all the things I say/No, I never would be heard, no, without

the money game!" So Karl upped the ante on the arrangement:

"I said, 'John, get a fuzz-tone. And I want Kit to do

his boom-bum-bum-boom,' which is basically a strip beat speeded

up. And I said, 'I'll just do the piano more classical.'"

Kit laid down a vicious lead vocal, and the track rocked harder

than anything the band had previously committed to vinyl.

The two "statement songs" were paired on a 45 that

August, but 'Look Away' rode on the A-side in a most altered

state. As Karl laments, "I rode with Harold Lipsius to

New York, and we took it up to a studio - I don't remember

which one ... we spend the afternoon while we watch the engineers

MURDER MY BABY! And I told them, 'You murdered my baby!!!'

And the engineer looked at me and he said, 'Ah, you Beethovens

are all alike! Look, you hand me a seven-minute song, I gotta

cut it down to three - don't worry so much! It'll sound great

on the jukebox!'" That engineer was wrong. The 45 edit

of 'Look Away' was indescribably horrible; the word "abomination"

does not even come close to explaining what a pointlessly

embarrassing train wreck it was. Not surprisingly, it tanked,

and that proved to be the last straw for the band. They were

disillusioned that they had not become bigger after so many

years and depressed that Jamie could not build on the new

hope offered by the success of 'Won't Find Better'. They'd

had great expectations for 'Look Away', but the failure of

that song put them further in the dumps than they'd been in

a long time. They were ready for a change, and one was about

to come their way thanks to an extremely unlikely source.

PARAMOUNT

In November of 1970, Kit received a phone call from a producer

who wanted to offer the band a deal with Paramount Records.

That producer's name was Bob Finiz. Finiz was now working

for Koppelman-Rubin Productions and had contacts at Paramount,

a label he believed could promote the Kats better than Jamie.

The band still felt the sting of the lawsuit, but Finiz made

nice with them and set up a meeting with Charles Koppelman

in New York. Koppelman asked the guys to return to the Big

Apple and do a live show for some of Paramount's staff, which

they did in early 1971. Duly impressed, Paramount agreed to

sign the group, who reverted to the name the Kit Kats because

that was still the name under which they were the biggest

draw. [28] Finiz took

them into Media Sound Studios in New York to cut their Paramount

debut, 'Taking My Time'. It was a simple number, but Kit's

lyrics really packed a punch. With lines like "People

talkin' and they wonder why I don't have time to make some

money," and "Taking my time, taking it slow/Nobody's

shown me where to go," it was the unmistakable anthem

of the average American 20-something: he's confused and desperate

to find a direction in life, but people would rather bug him

about it than actually help him find something he can really

sink his teeth into. You might consider it a close cousin

of the Beach Boys' 'I Just Wasn't Made For These Times', except

Brian Wilson was in his twenties when he wrote that

tune, while Kit was a full 31 years old when he penned the

lyrics to 'Time'! And Kit's inclusion of the line "I

fill my body with the magic wine, I wonder why my life's still

lonely" raised Karl's eyebrows: "I listened to this,

I said, 'What, are you on drugs now?' He said 'No!' [laughs]

I said, 'Your lyrics have changed! It's no more June, croon,

spoon, honeymoon crap!'" Sadly, the potent lyrics

and Karl's strong melody were sabotaged by Bob Finiz, who

insisted on an annoyingly gimmicky arrangement. Finiz called

for tempo changes, abrupt stops and starts, and a fast cadence.

Karl: "I said, 'For Christ's sake! It's not a march!'

By the time it was finished, it sounded more like I could

picture the seven dwarves marching …" Karl does

admit that he asked for the goofy horn overdub (which was

done at Finiz's house in Cherry Hill, New Jersey), but he

also admits that it "sounds dumb now." There were

some tasty Rock-Si-Chord passages, but Finiz edited out the

lengthy psychedelic instrumental breaks so that the song would

clock in at slightly over two minutes - an unnecessarily short

running time for an early '70s single. Still, 'Taking My Time'

had a lot to offer, and with the promotional backing of a

larger label it stood a good chance of taking off. Released

in the fall of 1971, it went absolutely nowhere. "Not

a great promotion staff, Paramount," moans Tom Kennedy.

"That was Famous Music, and I don't think they could

deliver lunch in a bag."

Too bad, because the B-side of 'Taking My Time' was an especially

delicious feast. 'That You Love' came totally out of left

field, with lyrics like "I know what I have to be and

it offends you/It ain't natural, so you say/For someone to

love my way/If you think I'm wrong, I wish you'd understand:

it's not who you love, it's not how you love, it's that

you love." The song was of course light years ahead of

its time, and it was written solely by Karl [29],

which is quite surprising in retrospect. After all, Kit had

clearly developed an interest in statement songs, but what

possessed Karl to get on his soapbox as well? As it turns

out, Kit had something to do with it. One night in 1971, he

invited Karl to see the Frisco Follies, a gay revue featuring

male performers who impersonated female singers such as Barbra

Streisand. Karl was not terribly keen but Kit convinced him

to give it a chance; Karl ended up enjoying the show and was

particularly moved by what one of the performers said at the

end: "Just remember, ladies and gentlemen: It's not who

you love; it's not how you love; it's that you love."

Karl was in complete agreement: "I said, 'You know? They

are RIGHT! Absolutely right! It's that you love! Nobody's

ever hurt anybody with that.' And it was sometime after that

I went down just a few months later and I came up with that

song. And I thought, 'I'm gonna write something in defence

of gays.'" But in his mind, Karl had a crisis of intentions:

why was he writing a song in defence of gays? He wasn't gay,

and the only gays he knew were people he talked to in the

music business. After thinking it through, he came up with

the best reason anyone in his position could come up with

for writing such a song: "All of a sudden, I felt pity

for people being treated shitty just because they are who

they are." Along those lines, Tom Kennedy offers some

intriguing insight into his old friend's character: "Karl

has very high standards. I mean, he is a beautiful man, and

I'm sure that even if he didn't feel it was a lifestyle, it

was something that should have been voiced."

But like Karl, the rest of the Kit Kats were straight - so

how did his bandmates feel about the song? "They didn't

say a word about it, they just went right along with it,"

reports Karl. "They never snickered or laughed or anything.

I think as musicians, you're more broad-minded. I don't know

why." Even Big John had no problems singing the song

in the first person, as Karl happily recalls: "Even I

said to John, 'If anything would ever happen with this song,'

and he says, 'Ah, what the hell do I care? Anybody that knows

me knows where it's at! I don't give a shit!' John used to

go like that. His favourite expression was, 'Who gives a rat's

ass!'" Soundwise, session players sat in on bass and

drums (the legendary Gary Chester on the latter) to get a

better feel for the Latin beat, and John ripped out a mean

fuzz-tone while the group's harmonies took on a mournful tone.

Sadly, Bob Finiz was too hung up on 'Taking My Time' to see

that he had an even greater gem staring him right in the face.

Riding on the flip of a flop doomed 'That You Love' to oblivion

- but maybe that wasn't all bad. John's voice was so high

and sweet on this track that some of the few people who heard

it thought it was the work of a female singer. Consequently,

lines like "You like to knock me on the floor […]

Do you beat up women, too?" were rendered inane.

KIT QUITS

Paramount had promised the guys four singles a year, but the

company was slow to make good on its promise. Karl had written

a painfully frank, Jimmy Webb-styled ballad entitled 'Can't

Go Home No More', a song that was simultaneously beautiful

and devastating. The Kit Kats' recording featured Karl's plaintive

vocals and instrumentation primarily by Burt Bacharach's orchestra.

Karl was excited about the song, and he wasn't alone. "They

all raved about it," he remembers, "even the guys

in the band and even Gary Chester, who used to record with

Frank Sinatra. He said, 'I'm not hypin' you, kid, but if Sinatra

wasn't in retirement, he would record this song. If it comes

out, he may yet.' Musicians don't talk that way, you don't

get the phony baloney stuff from musicians." 'Can't Go

Home' was slated to be the next Paramount single, but with

the label taking its time, taking it slow, the group had a

chance to unravel. For no apparent reason - other than being

in the same band for too long - Kit and John became like oil

and water. The Kats' plans to record more material kept getting

delayed as a result of the internal bickering. With the two

longtime friends now at each other's throats, things came

to a head and one night Kit, the founder and leader of the

band, announced that he was quitting. Ron and Karl thought

Kit was being disingenuous until he got a new job and bade

farewell to the audience on his last night. So it happened

on July 4th, 1972 - ten years to the date after Kit, Ron,

John, and Karl had become the foursome we all know as the

Kit Kats - Kit Stewart was history. That was the death knell.

Paramount lost interest in the group and never released 'Can't

Go Home' or anything else after 'Taking My Time'. [30]

Karl's brother Rick, who'd just returned from Vietnam, replaced

Kit on drums and vocals, while John took over the bookings.

The Kit Kats, barely together anymore, found it harder to

stay alive. People were no longer as interested in the same

old band, as a befuddled Karl admits: "We were still

a big draw with the crowd that knew us all along, but the

younger crowd, not so much! Don't get me wrong, it was still

a lot of young people coming in to enjoy the group, but we

started getting to the point where simply because we'd been

around so long, people were saying, 'Are they still together?!?'

It was like we'd been together too long! And I thought,

'This is insane! We still sound as good.' But it's like, 'What

are you guys still doing here?' And that was our biggest complaint

from people! We'd work out new songs, we'd do this and that,

and it just didn't matter! It was like, still the same band."

They'd get offers from record companies but some Kats, still

burned from their experiences at Jamie and Paramount, always

refused to take the bait. In early 1973, John and Ron had

a pointless, heated exchange that led John to fire Ron in

a heartbeat and replace him just as quickly with Billy Cornelly.

Though Cornelly was a nice guy, Karl was annoyed that John

fired Ronnie without even consulting him; it was yet another

sign of disintegration. Kit, now working with a booking agency,

offered to help his former band, but Karl was still irate

over Kit's departure and did not accept this olive branch.

It was just too much of the same thing until fate struck a

nearly deadly blow.

In March of 1974, Karl was suddenly found to have four bleeding

ulcers; he spent St. Patrick's Day having surgery. As is often

the case with tragic incidents, Karl's near-death experience

brought him and Kit closer again. Karl picks up the story

from here: "Kit was with this agency, and he said, 'What

are you gonna do with your life?' And I said, 'I don't know.

I'm recovering from an ulcer operation.' And he said, 'You

gonna go back with the Kit Kats?' I said, 'No. I've already

let Big John know I'm not gonna return, and John said, "I

had a hunch you wouldn't." I don't want that life anymore,

Kit. I wanna settle down.' I had a serious thing here. The

doctor said I was two hours away from being dead. Here I was,

32 years old and it was almost over. I had a lot of time to

think, what do I wanna do with the rest of my life now? And

the doctor says to me, 'You've had a good life. You know,

wine women and song' - the doctor looked me in the eye and

he said, 'It's time you start growin' up.' And I felt highly

insulted, but he was right. I'd been longing to settle down,

I never really had a solid family, I thought maybe I'd like

to have my own, and I did." With Karl out of the picture,

the band struggled on with a new pianist but broke up shortly

thereafter.

In 1976, Kit, John, and Ronnie reunited with a new keyboardist,

but they invited Karl to sit in with them for one night. He

happily accepted the invitation and had the time of his life

as a born-again Kit Kat - but just for that one night. By

this point, Karl was playing easy listening and show tunes

at a resort in Lancaster, and though he was more excited about

rockin' and rollin' with his old buddies again, it was not

enough to convince him to give up the ability to come home

to his wife and child every night. The Kit Kats were kaput

once again by 1977, and Big John went out as a solo folk artist.

Karl continued with steady jobs like the Lancaster resort

gig and even wrote some new songs with Kit at the beginning

of the 1980s. (Nothing ever came of them.) For a few years,

Karl and his wife Carolyn ran an ice cream parlour in their

Berks County, Pennsylvania community, where Karl had a room

in the back for piano shows. Thanks to a little wifely prodding,

he also auditioned for the role of Main Street Pianist at

Walt Disney World; he got the job and moved his family to

Florida for two years. Kit went into the produce business

and devised a clever idea to increase his veggie sales: dressing

up as a giant carrot. It's not surprising that this "Carrot

Man" idea came to him around Halloween (of 1982 or '83),

and as he told Steve Harvey in 1989, "I always loved

carrots and I always thought that they were the one things

you held out in front of horses to get 'em to go, and people

in corporations always said, 'Offer a carrot as an incentive,'

you know, the old - it's an expression." When people

started asking him for nutritional information, he did some

homework and expanded his Carrot Man act into an educational

song-and-dance show. He even made tapes with songs about nutrition

(he did 'Liza Jane' as 'Lima Bean'), and in 1986 he decided

to pursue the Carrot Man act full-time. And this is where

the Kit Kats re-enter the picture.

REUNION

"I was looking for a way to generate a lot of money

to put into my Carrot Man idea," Kit explained in 1989.

"[People I talked to] always said to me, 'Put the Kit

Kats back together! Put the Kit Kats back together!!! That's

the thing to do. The time is right, oldies are hot, you guys

could really do it!'" It wasn't the first time that Kit

had tried to re-form the original band, but it was

the first time that Karl missed the group enough to want to

rejoin. Karl would do it only if John would do it, and the

feeling was mutual. [31]

But for various personal reasons, Ron did not participate

in the reunion. This was probably for the best, as Karl reports:

"Ron stayed married to the same woman all the time. He

had children, he was a good family man, he was a good husband

and father. And I know darn well they weren't that crazy about

him going out there again. I know once he was out of the Kit

Kats, his wife was much happier." The band hired Dave

Ryan to be the new bassist for the Kit Kats and began rehearsing

in December of 1987; unlike Ron, Dave was a singer and even

sang lead on some numbers. Once again, Kit did the bookings;

the first gig was at Pennsylvania's well-known Immaculata

College on February 22, 1988. But even from the start, the

guys could not recapture the magic of the '60s. Karl: "It

was no longer the old days, where you worked, like, five,

six nights in the clubs. By now, in the late '80s, everything

was one-nighters. Times had changed and so what we did was

work one-nighters, and in the summertime we worked a place

called The Bent Elbow down in North Wildwood. And that again

was weekends."

That wasn't the only problem, for by July, Kit was out of

the band once again. In 1989, Kit recalled that the reunion

broke down so quickly because his bandmates became disillusioned:

"Our first time around was wonderful! People comin'

out of the woodwork, it was incredible, it was so exciting!

And then the second time around, it wasn't as exciting anymore.

So it started to filter out. It became [pensive pause]

not a good situation. So I became Carrot Man again. Simple

as that." Kit also believed he was somewhat more ambitious

than the rest of the Kats. For one thing, he wanted to record

again, but the other Kats were content to do as many live

gigs as they could scrounge up. Kit also faulted his bandmates

for lacking patience in the face of disappointment: "If

everybody woulda hung in there, we coulda overweighed all

that and came back again because our band had talent.

REAL talent. I don't mean bullshit, I mean real talent.

And the talent is still there. REAL talent. And talent,

and persistence, and perseverance will override every storm

in the land. Every one. Without that, there's nothin'. Talent

without discipline is meaningless!"

Today, in 2006, Karl remembers things somewhat differently:

"John and I fired Kit. [heavy sigh] We were no

longer the Four Musketeers, it was every man for himself.

It was fun for the first two months, but after that it was,

I use the expression it was like being back with your ex-wife.

Too many unanswered issues, unsolved issues from the '60s,

early '70s resurfaced." According to Karl, Kit sabotaged

the band by dreaming up all sorts of hair-brained schemes

to make money. For example, Kit created a guestbook for the

band's concertgoers to sign, ostensibly to create a new fan

club. He asked for each signer's contact info, but he also

asked signers to answer "Yes" or "No"

to the question, "Do you smoke?" He claimed that

he wanted to find work in venues where people didn't smoke,

but in reality he had made a "quit smoking" tape

and was trying to sell it to the Kit Kats' concertgoers! Such

shenanigans started to cost the band some very important gigs.

Karl: "Like, there was one, a big summer fair out here

in Lebanon [Pennsylvania] … it was gonna be a really,

really nice Memorial Day holiday thing at this park, good

money. All of a sudden, we're not working it. And Kit says,

'Ah, these guys, they didn't wanna pay the money after all,'

and everything. So I called the deejay that was in charge

of the thing, and I said, 'What's the story? I don't understand.

You guys have always been good.' He said, 'We were fine until